Serigne Mbaye knows the power of labels. And symbols.

Climate ripples and the rise of the right

When the seas rise in Senegal, so do the fortunes of far-right political parties in Europe. This is the story of how those seemingly unrelated things are connected.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

His friends call him the “Malcolm X of African immigrants.” His political opponents in Spain, where he lives now, falsely call him “illegal” and have suggested deporting him, despite his Spanish citizenship.

Still, he endures. Mbaye is now a deputy in the Madrid Assembly, having made the perilous migration from Senegal in 2006.

The rhetoric directed at him — both lofty and poisonous — demonstrates the powerful symbol he has become: an embodiment of sweeping global trends that are shaping the world.

As climate change heats up the planet, the pressure on people to leave their homes is increasing for those who are already struggling to survive. And where migrants see hope of a better future, far-right politicians see both a threat and an opportunity.

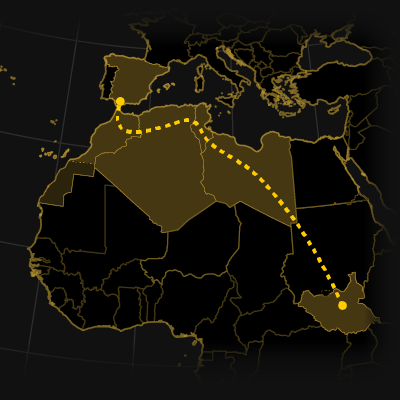

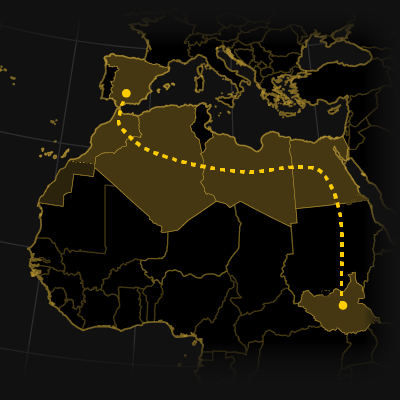

While these themes of climate change, migration and far-right politics ripple across continents, we are zeroing in on a route that touches three countries: Beginning in Senegal…

traveling through Morocco…

and on to Spain.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Mbaye’s migration story began in 2006, when he realized that salt water was inundating the fields that his father used to farm and that foreign trawlers were hauling away the catch he depended on as a fisherman in the Senegalese town of Kayar.

Kayar

Senegal

Life in Kayar depends on the sea. Fishing is the main game, and the ebb and flow of the tides provide a steady rhythm to people’s lives.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Today, Mbaye’s mother, Dior Diouf, is a revered matriarch in Kayar, managing a six-bedroom house full of children and showing a gold tooth when she smiles.

When she gets on the phone with her son, she calmly shares all of the requests from people in town who need money. This person has an unpaid electric bill. That one needs school tuition.

His reputation is vast.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

In the courtyard of a far more modest house, where Mbaye spent his childhood, his Aunt Ndye Toure insists that she always knew the boy would grow up to be something special.

“He was my darling,” she says. “A hardworking boy with a fighting spirit.”

Almost everyone in Kayar who talks about Mbaye uses that same phrase — a fighting spirit.

In Wolof, it’s “gnafé kat leu.”

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

“Even the smallest baby knows him here,” says Khadim Ngom, a local spear fisherman (in the black wetsuit).

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

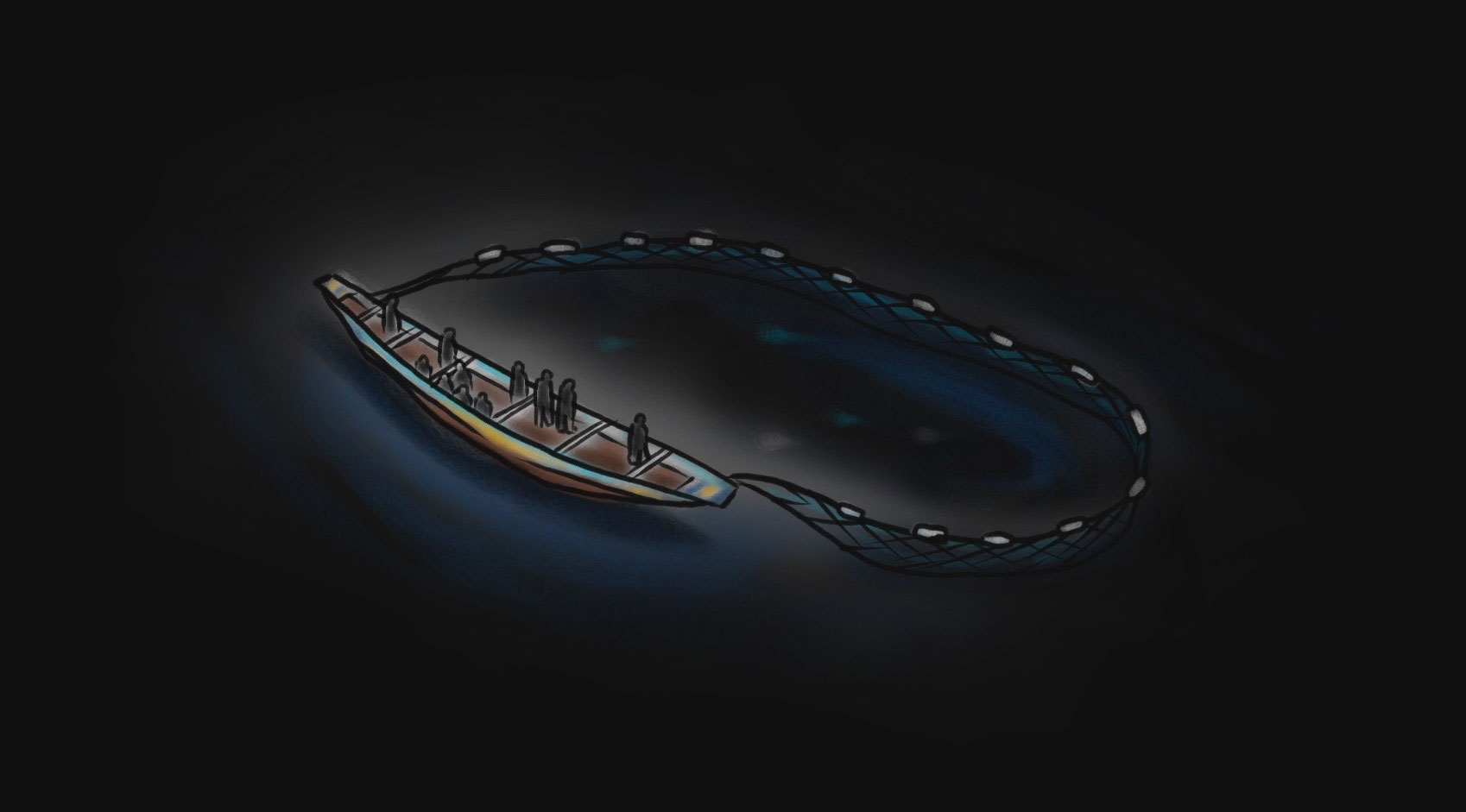

Brightly colored wooden fishing boats called pirogues provide the fishing income that Kayar depends on.

But the factors that spurred Mbaye to leave his home have only gotten worse.

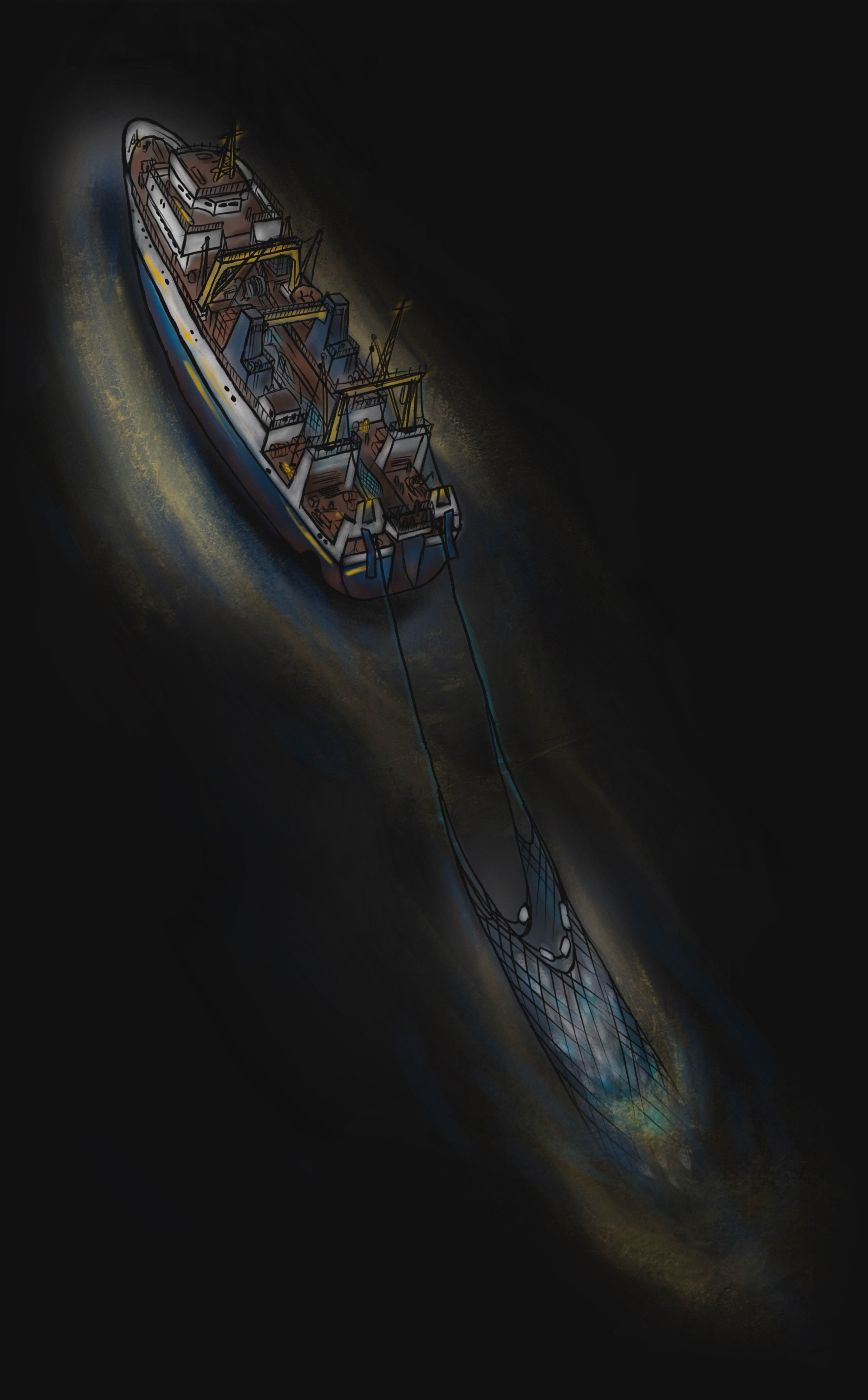

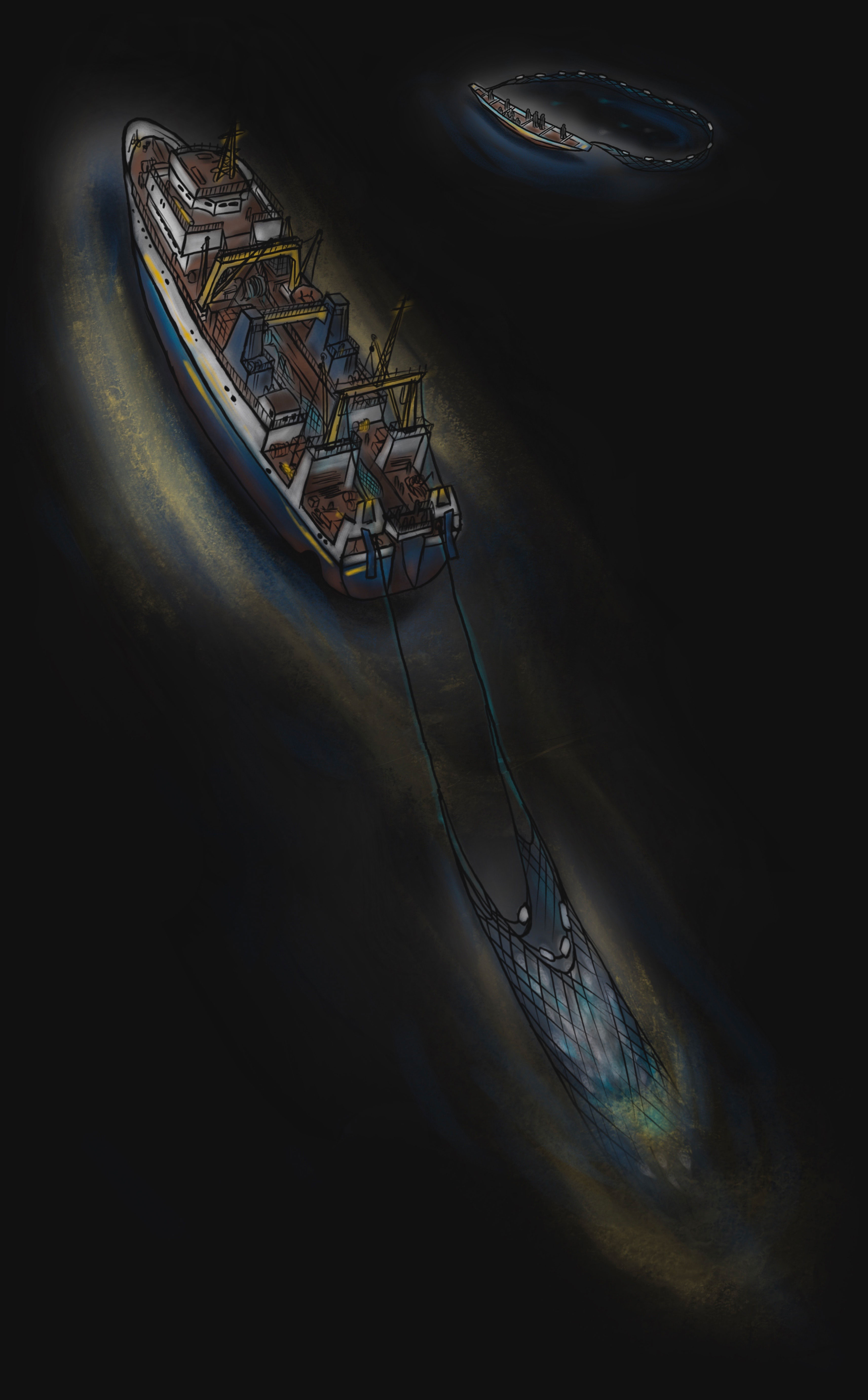

Overfishing from trawlers has decimated fishing stocks.

“It’s been 10 years since we saw sardines here,” says a fisherman named Serigne Mou Diop.

A pirogue that fishes for sardinella stock might be lucky to catch 300 tons of fish in a year, using large seine nets.

A trawler that drags an enormous net behind it is able to catch the same amount in a couple of trips.

Due to its size, it can also more easily sail farther in search of new stocks.

Some kinds of trawlers drag their nets along the seabed, damaging marine habitats as well as frequently catching non-target species that are then discarded.

Global Fishing Watch, a research nonprofit, uses publicly available transponder data to detect fishing effort.

The impact of trawlers is visible up and down the coast of West Africa.

apparent fishing effort

Hours spent fishing by trawlers in 2022, according to analysis by Global Fishing Watch.

0

100+

According to Global Fishing Watch, trawlers spent more than 160,000 hours fishing in Senegalese waters in 2022. That amounts to about 18 years.

About 88% of that fishing was from ships flagged to Senegal.

But a forthcoming study from ocean criminality expert Dyhia Belhabib showed that more than 50% of the Senegalese-flagged trawlers she investigated were owned by foreign entities — many of them Spanish and Chinese companies.

Additionally, trawlers can enter illegally from neighboring waters. The scale is hard to quantify, according to Belhabib, because foreign fishermen may turn off their transponders when entering Senegalese waters illegally. As a result, Global Fishing Watch also cannot track this information.

Trawlers light up the waters at night when fewer patrols are around. Senegalese fishermen call it New York City at night.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Out on the water, spear fisherman Khadim Ngom plunges under the waves with his mask and fins, weapon in hand.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

When he pops his head up at the surface, he says it’s too murky to see any fish. The trawlers have dragged their nets along the bottom, kicking up the dirt on the seafloor.

Like almost all of the working-age men we met in Kayar, Ngom tried to go to Europe. He left Senegal in 2006, the same year as Mbaye.

It was a nine-day journey on a boat with 137 people. They ran out of food before they made landfall in the Canary Islands.

But while Mbaye remained in Spain for years and became an elected political leader, Ngom was deported back to Senegal after just over a month.

Then there’s the problem of coastal erosion.

Climate change is eating at Kayar’s shoreline as warming oceans lead to sea-level rise. The ocean keeps coming closer.

Median annual shoreline

Each line represents the median position of the shoreline for a given year, according to an analysis by Digital Earth Africa.

2000

2021

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Where the water meets the land, a two-story concrete building has been exposed like a dollhouse.

Ngom says it was a warehouse for ice to preserve the fresh catch. In 2019, a flood demolished the building.

Experts refer to climate change as a vulnerability multiplier.

It exacerbates the pressures of overfishing and poverty, pushing people here to leave.

While 80% of migration happens within Africa, many attempt the journey to Europe. They are overwhelmingly men.

We heard a range of stories about the journeys people took.

Note: Paths shown are directional, not exact routes.

*He shared only his first name because of his immigration status.

*He asked us not to use his name because he doesn’t want his family to know how bad his life is.

The European Union has spent billions of dollars on security infrastructure to keep African migrants out of Europe. One place you can clearly see that is on the southernmost land border between Spain and Morocco, at the cities of Nador and Melilla.

Nador

Morocco

Melilla

Spain

Melilla is an enclave city of Spain. Though it sits on the northern edge of the African continent, it is technically part of Europe, surrounded by Morocco and the Mediterranean Sea.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

People who grew up in Melilla remember passing back and forth between Spain and Morocco easily. Journalist Irene Flores says that when she was a child, there was no fence and no border. “It was like a free crossing through a checkpoint.”

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Today, the fences are four layers deep, patrolled by armed guards. That armor is paid for by the European Union to repel people who have traveled thousands of miles to enter this fortified city.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

This situation gives Morocco a lot of leverage over Europe. Moroccan authorities have the power to crack down on migrants or look the other way and let people through the fence.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

So whatever Morocco wants from Europe, whether that’s money or control over the disputed territory of Western Sahara, people trying to reach Melilla become convenient pawns that Morocco can use in this geopolitical chess game.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Right now, the European Union is urging Moroccan authorities to take a hard line against migrants. And that is exactly what Morocco has done.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

In the Moroccan city of Nador, several sources told us that people from sub-Saharan Africa cannot rent a place to stay. “Authorities have forbidden it,” says Moroccan human rights activist Omar Naji.

“If someone rents a room to a sub-Saharan migrant, they can be prosecuted for assisting. You could be asked for your papers in the street, stopped for the color of your skin.”

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

When Moroccan officials find people camping in the mountains around the city, authorities sometimes burn their campsites to the ground.

Javier Bernardo/AP

Javier Bernardo/AP

On June 24 last year, a group of about 1,500 people who had been camping in the hills around Melilla stormed the border fence. Moroccan police fired rubber bullets and tear gas at them.

Javier Bernardo/AP

Javier Bernardo/AP

According to Morocco and Spain, 23 people died. But the number could be much higher. Human rights groups say more than 70 others who ran at the fence that day are still unaccounted for.

Morocco has refused to allow an independent investigation. And the Spanish interior ministry declined to comment about the events of that day when contacted by NPR.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Steven Khon Khon was one of those who rushed the fence that day.

He and his brother had left South Sudan in 2016 and tried many times to reach Europe by sea from Libya. “The police catch me,” he says. “Sometimes when you’re caught, you’re put in prison six months.”

They eventually decided to try this land crossing instead.

On June 24, Steven made it across the border into Melilla. His brother did not.

Now they are on opposite sides of the fence, in two different countries.

Huelva Province

Spain

Those who successfully make it to Melilla are often transferred to mainland Spain, where they can apply for asylum or a work permit. Many find jobs, formally or informally, on the strawberry farms of Huelva province of Southern Spain.

The town of Palos de la Frontera is home to 10,000 people most of the year. That population doubles during the harvest season, according to Manuel Piedra, a farmer who leads an organization of small strawberry producers in the area.

Workers come from across sub-Saharan Africa to work the fields. Even here, climate change is having an impact. The harvest now begins in December rather than February, Piedra says.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

In 2006, Abdulai Beye gave up his life as a fisherman in coastal Senegal to board a boat destined for Spain. He worked 10 years in Spain without papers, and without seeing his wife or son. Now he can go back to visit, and he sends them 2 euros out of every 5 he earns.

“This is harder work, but you can make more money here than in Senegal,” he says. He spends long days bending over raised beds, planting seedlings in the fall and picking berries in the spring.

When he eats fish in Spain, he sometimes thinks about where his meal came from and wonders whether a commercial trawler from Europe pulled it from the Senegalese waters he used to call home.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

The settlements where many of these farmworkers live offer a vivid look at the distance between the dream immigrants have of Europe, and the reality.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Mamadou Diop left Senegal in 2019 and lives in a rough shack off the grid, surrounded by hundreds of similar structures.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

In Senegal, his family lives in a house with electricity and indoor plumbing. Here, he has none of that.

His 4-year-old daughter says, “Papa, when are you coming home?” He tells her, “When I have my papers.”

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Spanish law says people are eligible for permanent residency after they’ve been working three years, as long as they meet certain conditions. That’s more generous than the U.S. and many other countries, but the reality for these guest workers is that it often takes years longer.

The reasons can be varied. Farmers may deny paperwork attesting that they have worked there, or run-ins with police might set back the clock.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

As difficult as life here is, Hope Joseph says it’s better than the alternative in Nigeria, where she’s from. “At least my mother won’t be hungry,” she says, adding that she can feed her by sending money back to Nigeria. “Back in Africa, I cannot feed anybody.”

Her family calls her a “pillar,” which makes her proud, even if she struggles to survive in the chaos of working without papers in Spain.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

These settlements provide useful talking points for anti-immigrant politicians.

“We’re sorry to see the situation that many migrants experience in Europe,” says Rafael Segovia, the local president of the far-right Vox party.

He specifically worries that international refugee law will begin to recognize people displaced by climate change.

“If we hope to defend our cultural identity, we need to reject the idea of the climate refugee,” he says. “If that notion is accepted, all these illegal migrants would have to be admitted because they would legally be considered refugees.”

The rise of the Vox party is part of a broader trend. Anti-immigration attitudes have caught hold across Europe and beyond, as political groups feel emboldened to portray migrants as a threat to national identity.

Madrid

Spain

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

In Spain’s capital of Madrid, the first job many Senegalese migrants take when they arrive involves constant danger and running from police.

“Manteros” are named for mantas, the blankets where they spread out their wares in plazas, on sidewalks or in subway stations. The inventory typically includes knockoff designer handbags, tennis shoes and sunglasses.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

It was the first job Serigne Mbaye had when he arrived in Spain in 2006.

“I thought, is this what I came to this country for? This can’t be my destiny,” he recalls. “But there’s nothing else you can do.”

He had the bad luck of being arrested the very first day he went out to sell things.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Then he got organized.

After four years of moving between various jobs, including construction and elder care, Mbaye secured his citizenship and helped open a restaurant.

In 2015, he helped establish the first manteros collective.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Today, as one of the few Black people to have succeeded in modern Spanish politics, Mbaye no longer has to run from police.

Walking down the street through Madrid’s immigrant neighborhood of Lavapies, he’s all handshakes and high-fives. Everyone seems to know him.

But his prominence as a deputy in the Madrid Assembly also makes him a target for right-wing politicians.

Ricci Shryock for NPR

Ricci Shryock for NPR

He feels it, but it doesn’t deter him.

“Honestly, it is a lot of pressure. That’s why I have to think carefully about every single word, every step I take,” he says.

“Because it’s not just me. It’s the whole community.”