Storing Waste

David Gilkey/NPR

A byproduct of fracking is a thick, muddy liquid called "flowback." It's a mix of water, chemicals and minerals.

Storing Waste

What Do You Do With Polluted Wastewater?

Millions of gallons of water are held in a storage pond until they're mixed with sand and chemicals, and pumped down the well to burst open shale. About 30 percent of what's sent down a well comes back up within a month. A good deal of the rest may come up over a period of years. But the fluid coming back up may have absorbed salts and heavy metals found deep underground, making it even dirtier.

Early on, a big question was what to do with all that leftover liquid. These days, much of it is temporarily stored in ponds or tanks, until it is shipped to other wells to be reused. Some of it may be pumped into underground disposal wells -- which have been linked to earthquakes.

There are still unanswered questions. How many times can you reuse waste fluid before it becomes too corrosive for the well? And years down the road, when there are no more wells to be fracked, what do you do with all the waste liquid?

Well Construction

Penn State Public Broadcasting

A cross-section of well casing shows layers of protective steel and concrete.

Well Construction

Are Gas And Fluids Leaking From The Well Shaft?

Wells are drilled with a number of safety measures to protect local water supplies. The steel pipe that lines the well shaft is much thicker near the surface than it is deep underground, and the outside of the pipe must be sealed with concrete both above and below the water table.

Nevertheless, flaws in construction do occur, and the layers around the well shaft can become damaged over time. A leak in these barriers could allow methane, frack fluid or salty brine from deep underground to contaminate the water table surrounding it.

Right now, there isn't a lot of monitoring of water tables or waterways that could spot potential pollution from leaks.

Fracking a well

David Gilkey/NPR

Pipes channel water and chemicals into a shale gas well during a frack in Pennsylvania.

Fracking a Well

What's In The Frack Fluid?

The ingredient list for frack fluid has been one of the most controversial issues surrounding shale gas production. It makes people uneasy that the industry refuses to say what exactly is in it.

In general, it's a mix of water, sand and chemicals that's pumped at high pressure down a well shaft to open up cracks in sandstone or shale. The sand helps keep the cracks open so the gas can continue to flow out. The chemicals do things like lubricate the well or break down minerals.

Frack fluid is 98 percent water. But a single well requires a couple of million gallons of water -- and that can add up to tens of thousands of gallons of chemicals. Additives range from substances found in household chemicals, like the antifreeze ingredient ethylene glycol, to corrosive substances like sulfuric acid, to carcinogens like benzene. The industry is increasingly revealing what's in the frack fluid, but some ingredients remain protected by law as trade secrets.

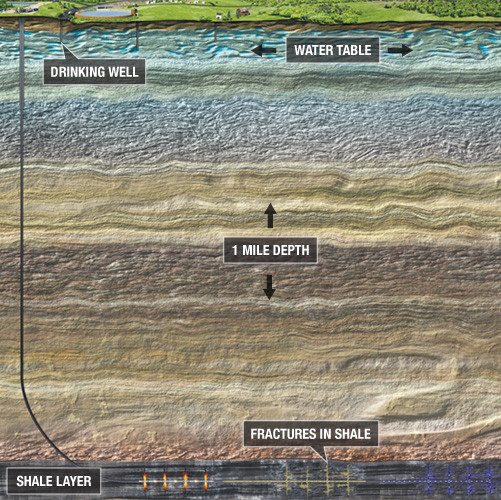

Drinking Water

Penn State Public Broadcasting

Shale is fractured deep underground, but water returning to the surface could escape through flaws in well construction.

Drinking Water

Are Shale Gas Wells Contaminating Backyard Water Wells?

Shale gas wells are sometimes as close as 150 feet to a house.

Especially around Pennsylvania's Marcellus Shale, people claim that the creation of these wells has somehow contaminated their backyard water wells. They say that when they turn on their kitchen sinks, their houses fill with a smell -- or that the water is so polluted they can ignite it with a match.

The fractures that release the natural gas are created a mile underground. Industry and the government think it's unlikely that gas or fluids are migrating a mile up through rock to contaminate water supplies. If there is contamination, it's more likely coming from flaws in the well shaft construction closer to the surface.

Well water contamination is difficult to prove, however. One way to test the connection would be to compare the pollutants in water before and after drilling began. Right now, the industry isn't required to sample local water before work begins.

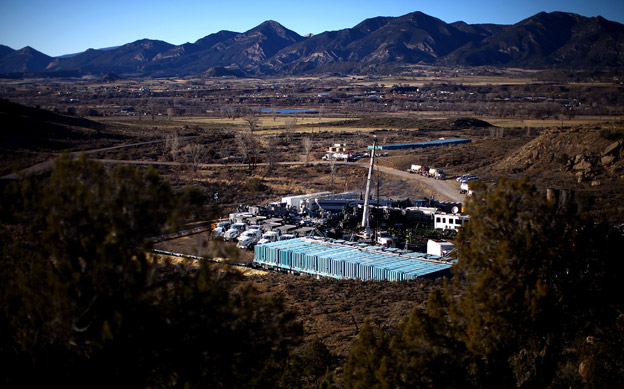

Sharing Water

David Gilkey/NPR

A mass of blue containers store water at a fracking site near the town of Silt, Colo.

Sharing Water

Is There Enough Water To Go Around?

The amount of water used to frack a single well would fill about eight Olympic swimming pools. In states like Pennsylvania that are rich with rivers, streams and lakes, that's not a problem.

But it's another story in drought-prone places like Texas and Colorado. Hydraulic fracturing puts additional strain on a water supply already taxed by agriculture, other industries and residential use.

Trucking Water

David Gilkey/NPR

A tanker truck carries water in Garfield County, Colo.

Trucking Water

Collateral Damage?

Sometimes pipelines are used to move water around, but usually it's a long line of trucks carrying water from the source, like a river, to the well pads or disposal sites.

Hundreds of trips may be required for each well, which are often located near homes in rural and suburban areas. All this traffic can damage roads, increase congestion and raise the risk of accidents — including spills of contaminated water.

Water Table

Shale Layer, 1 Mile Down

Shale Layer, 1 Mile Down