White Lies producers Connor Towne O’Neill and Graham Smith and reporter Andrew Beck Grace stand on the banks of the Alabama River with Jimmy Carmichael, who owns the land there. In the background is the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where the Rev. James Reeb marched on March 9, 1965, just hours before he was fatally beaten.

Chip Brantley/NPR

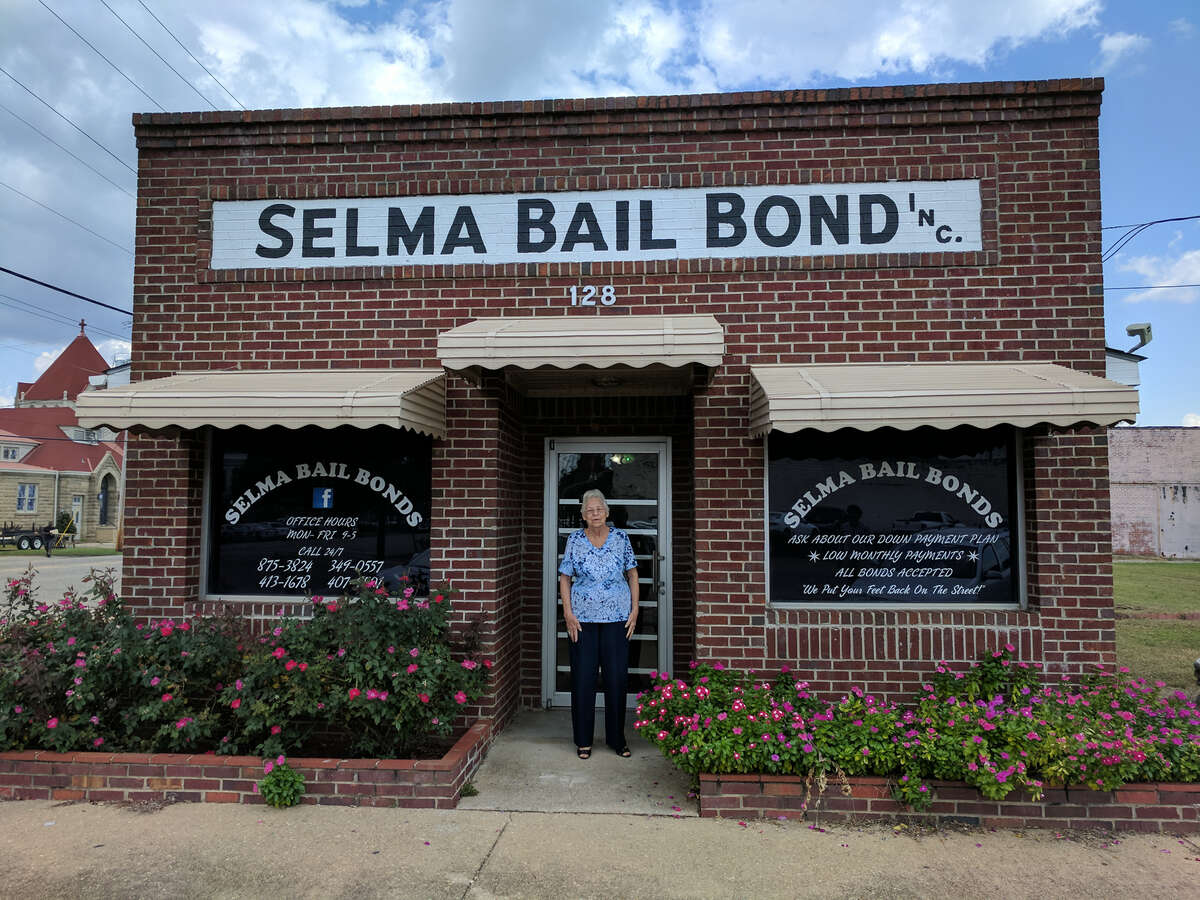

Frances Bowden stands outside her office at Selma Bail Bond. She works on the same street where, more than 50 years ago, a group of men attacked Reeb and his companions.

Chip Brantley/NPR

Smith talks with Randall Miller outside Selma Bail Bond, near where the three ministers were attacked in 1965. At the time of the assault, Miller’s family-owned funeral home was just down the street from Boynton Insurance Agency — the first place the ministers went for help after the attack.

Chip Brantley/NPR

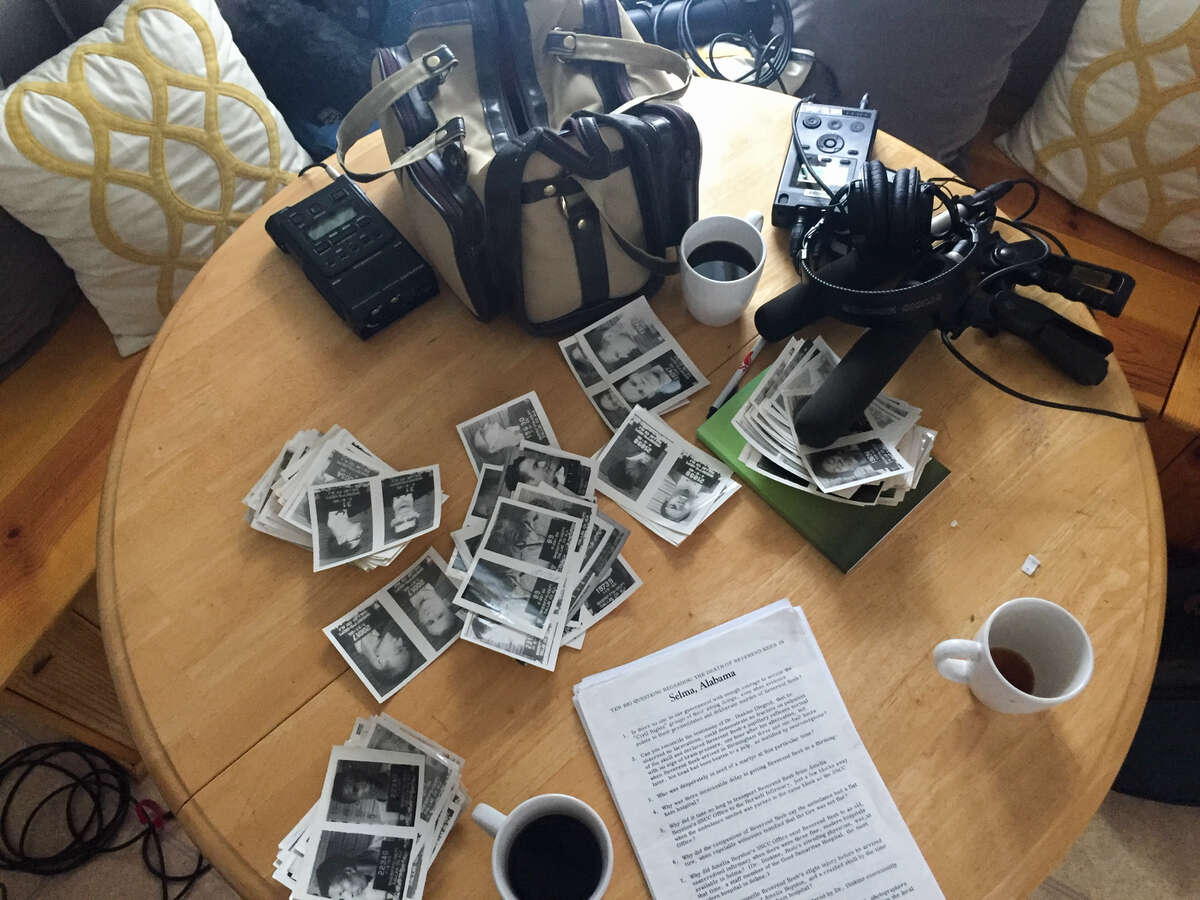

On a reporting trip to Asheville, N.C., to interview the Rev. Clark Olsen, the White Lies reporting team took stock of what it had — recording equipment, coffee and a conspiracy theory.

Andrew Beck Grace/NPR

Smith talks with Olsen, one of the ministers who was attacked alongside Reeb on the night of March 9, 1965. Olsen remembers holding Reeb’s hand at the Burwell Infirmary. "I was the last person, literally, in touch with him before he went unconscious," Olsen told NPR.

Chip Brantley/NPR

Reporter Chip Brantley interviews Dan Lane at a secret concrete bunker on a decommissioned Air Force base southeast of Selma, where Lane works as the deputy director of Craig Field Airport and Industrial Authority. "Y’all don’t even how weird of a place you’re even in," Lane told NPR. "Every layer of the onion gets even wackier."

Connor Towne O’Neill/NPR

Grace stands outside Gate 1 of the decommissioned Air Force base, where Jim Rutledge — known by most as "Turkey Bill" — had kept a secret hidy-hole that he jam-packed with empty suitcases, lots of shoes, and photos from car wrecks and crime scenes.

Chip Brantley/NPR

White Lies hosts Grace and Brantley rummage through Rutledge’s hidy-hole. They’re looking for a recording that Sol Tepper, a vocal segregationist in Selma, claimed to have made of the Reeb murder trial.

Connor Towne O’Neill/NPR

Brantley searches for the Tepper tapes in Alston Keith Jr.’s storage shed. Keith’s father and Tepper were both leaders of the Dallas County Citizens Council, an all-white group of businessmen and civic leaders who opposed any form of integration. Brantley wears his protective mountain climbing jacket, which co-host Grace laments does not protect Brantley from his own stupid ideas.

Andrew Beck Grace/NPR

The Dallas County Courthouse in Selma. Just down the hall, more than 50 years ago, three white men were acquitted Reeb’s murder.

Andrew Beck Grace/NPR

At a local antiques shop in Selma, a commemorative sheriff’s posse billy club is displayed next to counterfeit Confederate money. In 1965, Selma’s sheriff, Jim Clark, was known for his notorious posse — 300 able-bodied white men deputized in part to break up labor strikes and defend segregation.

Connor Towne O’Neill/NPR

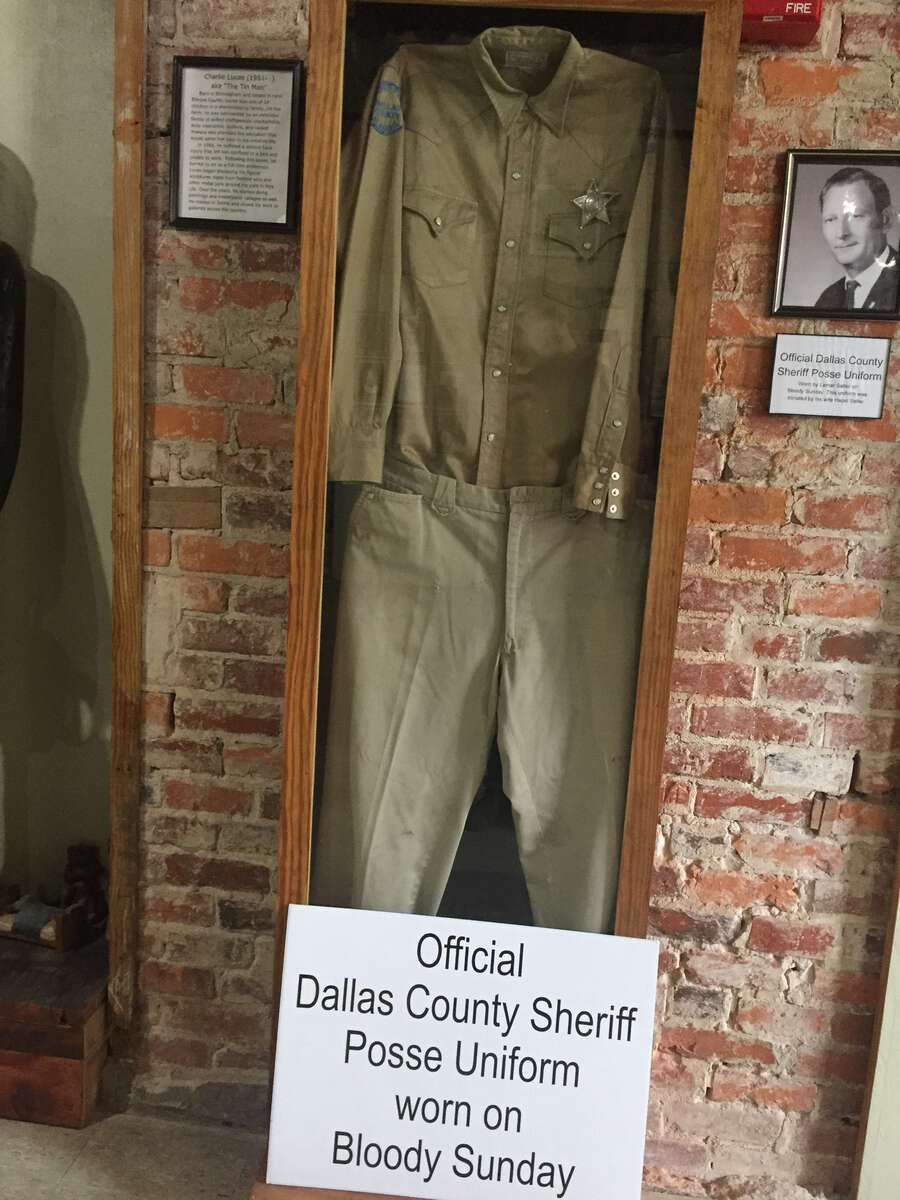

A sheriff’s posse uniform is on display at the Old Depot Museum in Selma.

Connor Towne O’Neill/NPR

Robert Gordon, who managed the estate sale for the family of Rutledge, shows the White Lies reporting team around his antiques shop and office. Rutledge may have helped Tepper make a recording of the Reeb trial.

Chip Brantley/NPR

Brantley interviews Roger Butler, a former employee of WGWC, the radio station where the ambulance carrying Reeb stopped for help when its tire went flat.

Andrew Beck Grace/NPR

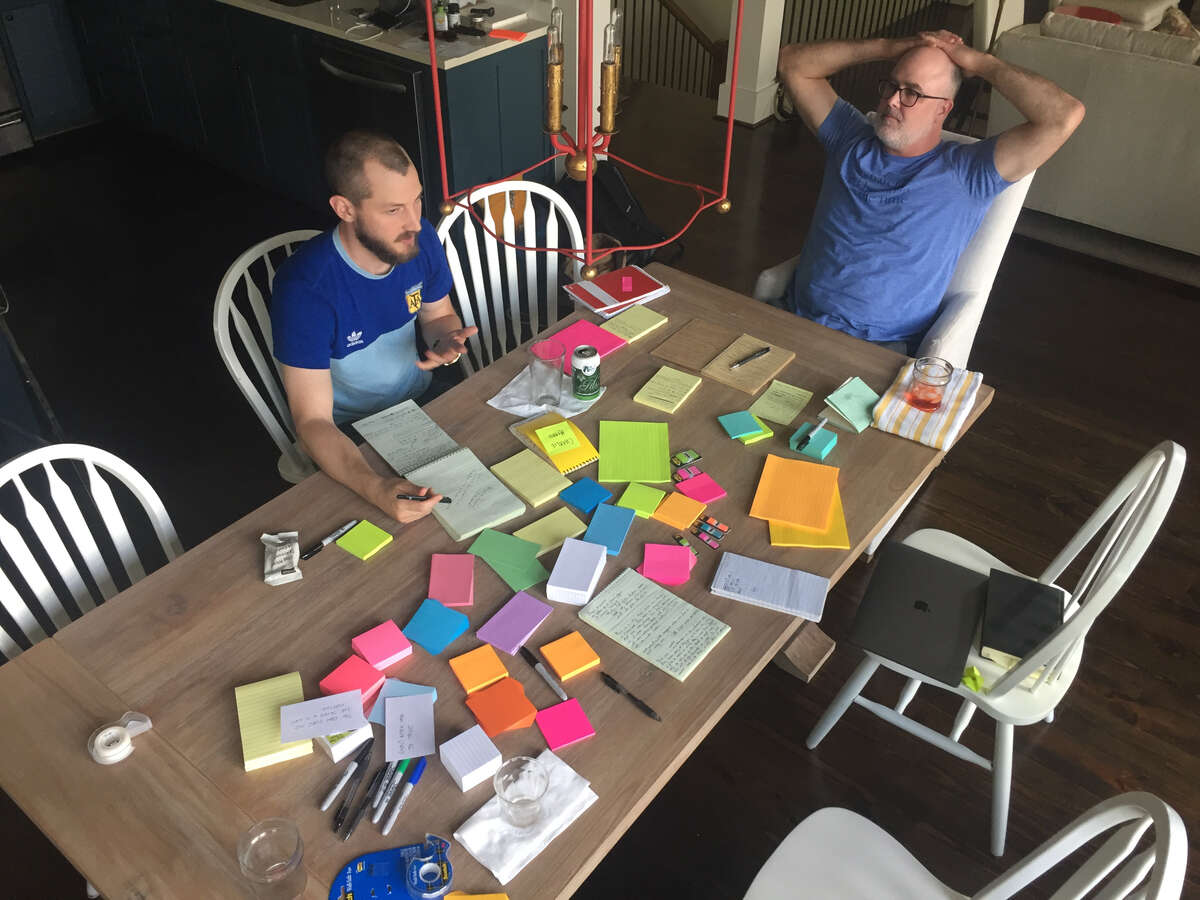

Towne O’Neill and Brantley pore over notepads and sticky notes during a White Lies writing session.

Andrew Beck Grace/NPR

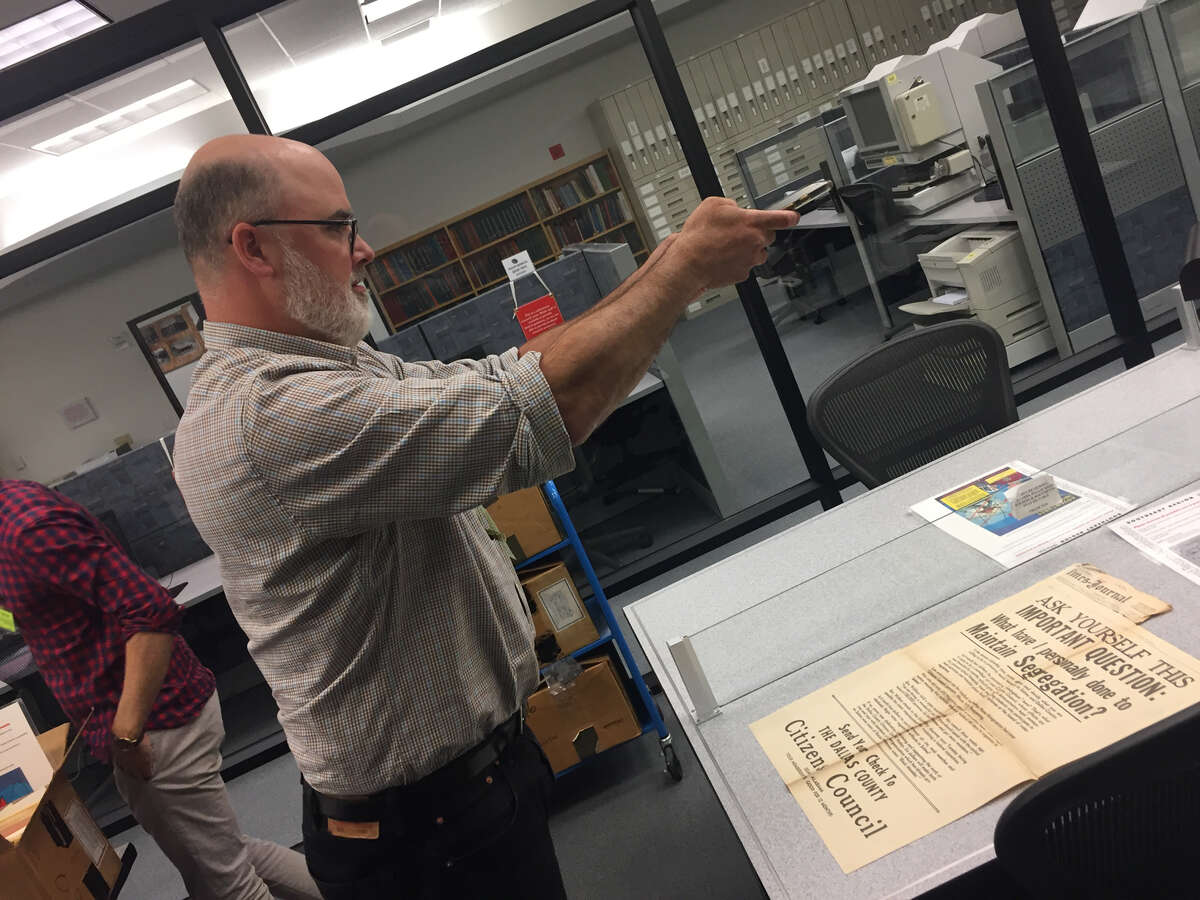

Brantley photographs a full-page 1963 pro-segregation ad published by the Dallas County Citizens Council.

Andrew Beck Grace/NPR

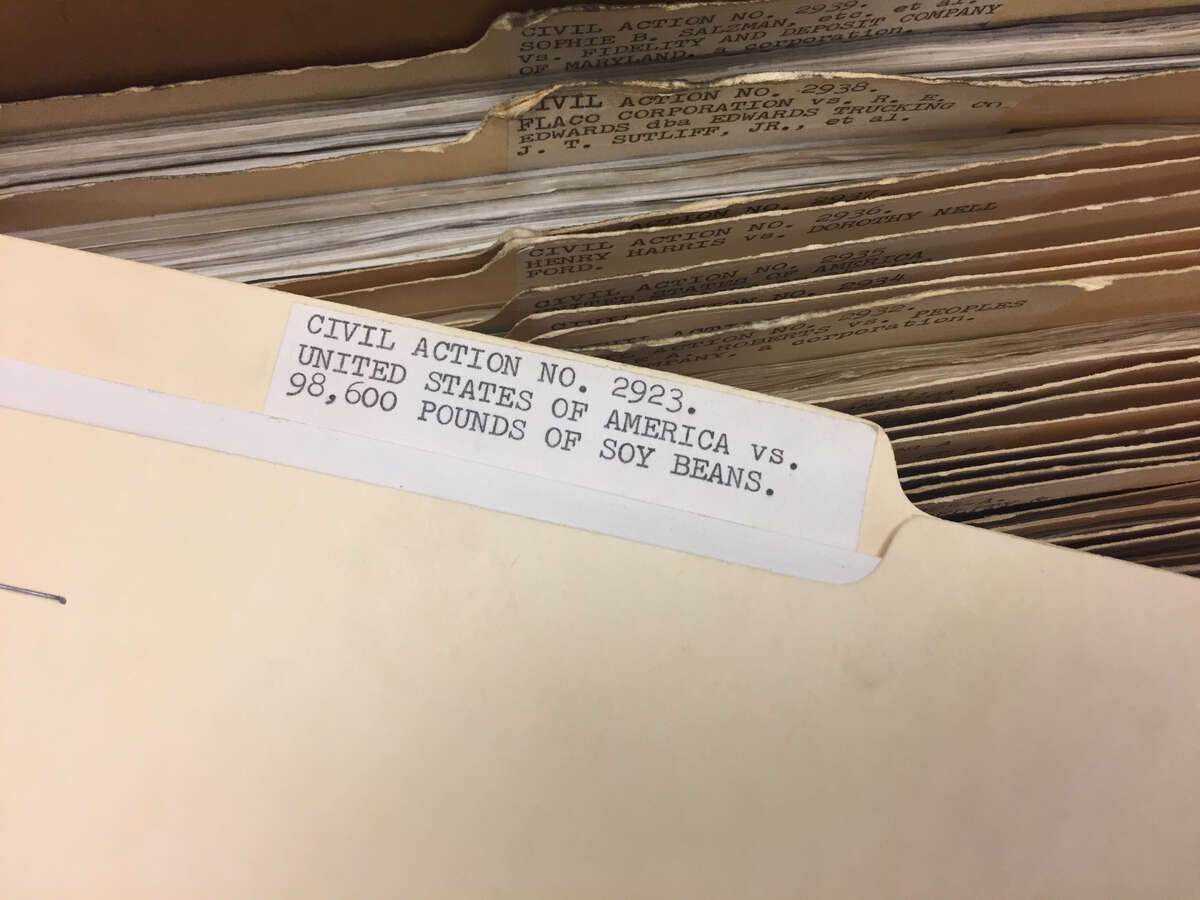

At the National Archives in Atlanta, the White Lies reporting team finds a reminder to, as former Newsday Managing Editor Alan Hathway once advised journalist Robert Caro, "turn every goddamn page.”

Andrew Beck Grace/NPR

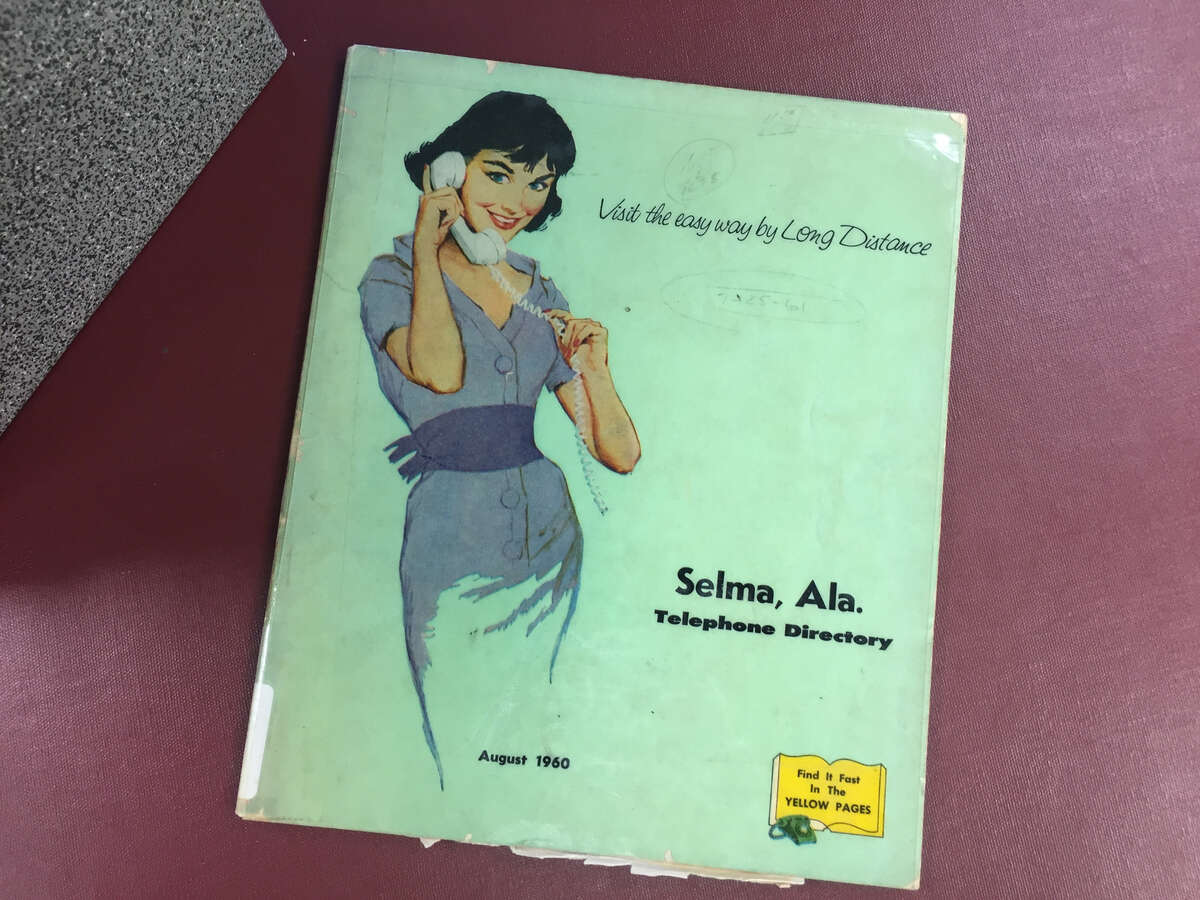

A local phone directory from 1960 sits on a table at the Selma Public Library. NPR relied heavily on archival material and historical artifacts to track down sources who lived in Selma when Reeb was murdered.

Andrew Beck Grace/NPR

Chuck Fager talks with Brantley in front of the old Selma jail, where Fager shared a cell with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. for a few days in February 1965.

Andrew Beck Grace/NPR

Brantley interviews Fager next to Jimmie Lee Jackson’s grave, outside Marion, Ala.

Andrew Beck Grace/NPR

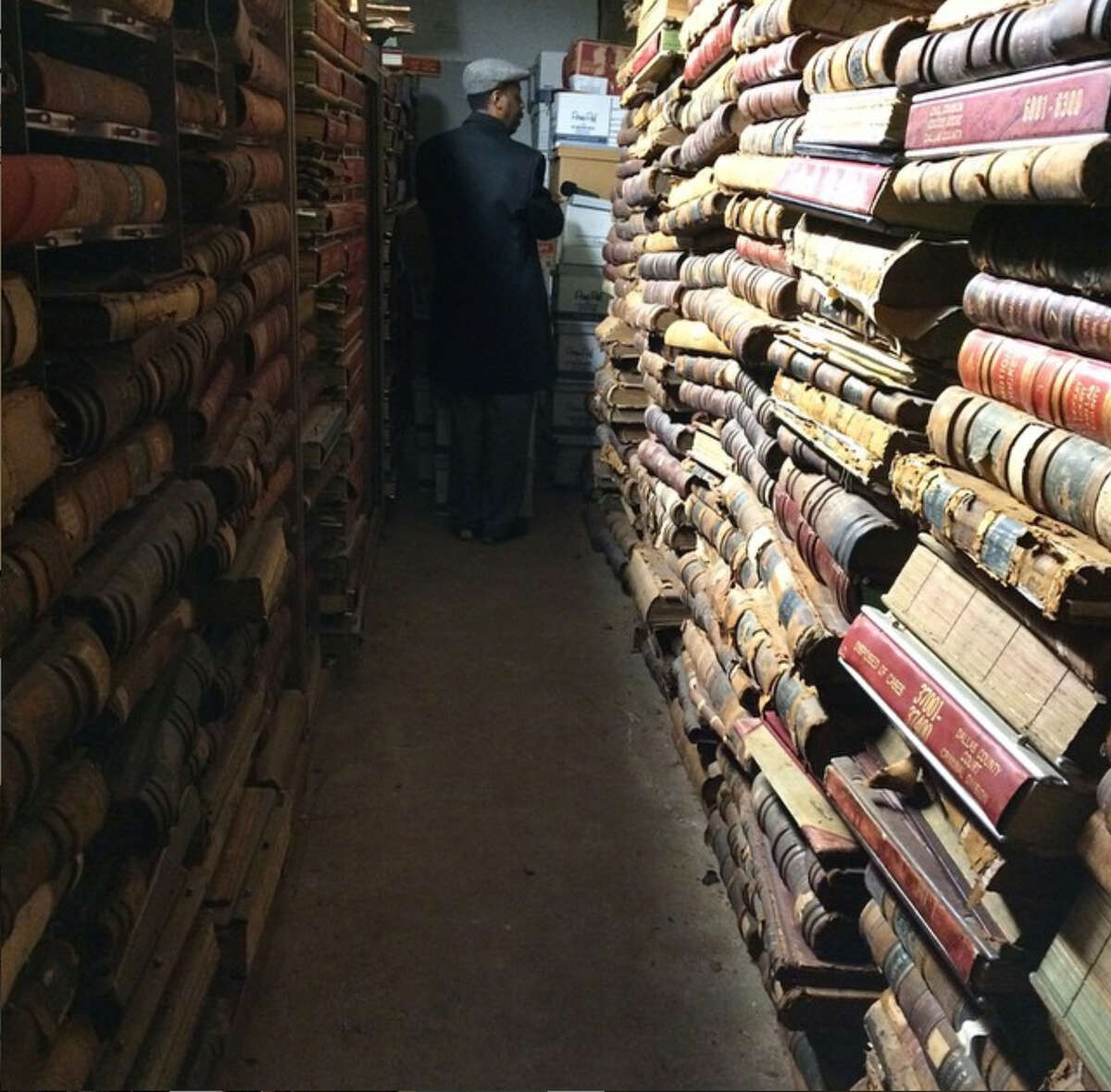

More than a century of Dallas County’s legal proceedings are jammed into a large, windowless metal shed behind the Enterprise Rent-A-Car on the outskirts of Selma. Prince Chestnut, who represents District 67 in the Alabama House of Representatives, stands in the archive, where the White Lies reporting team found property disputes, family disputes and booking logs — but nothing related to the Reeb trial.

Chip Brantley/NPR

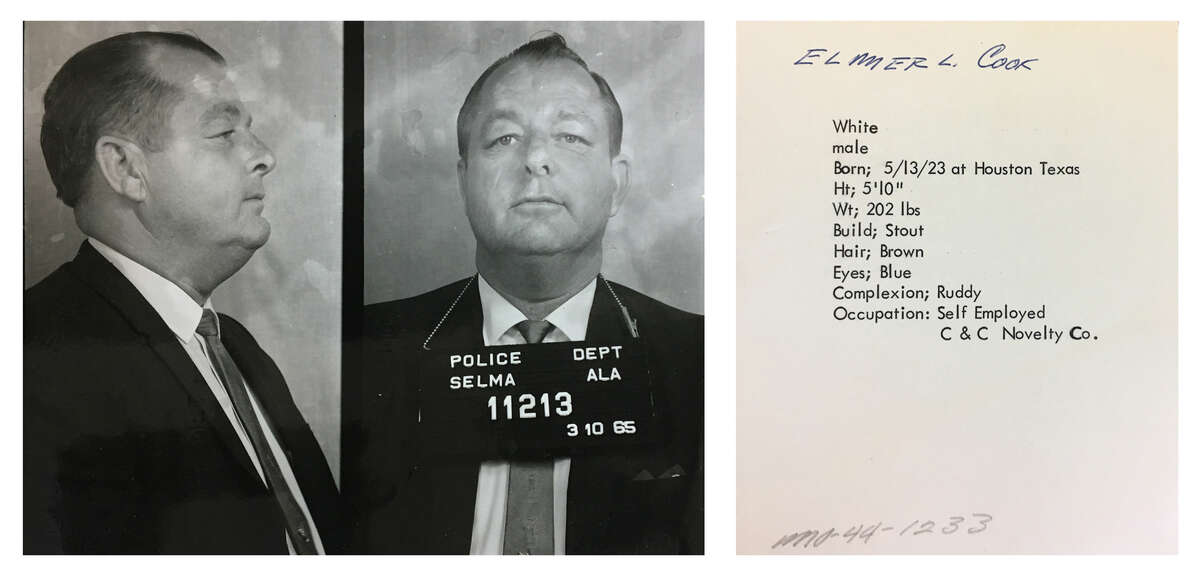

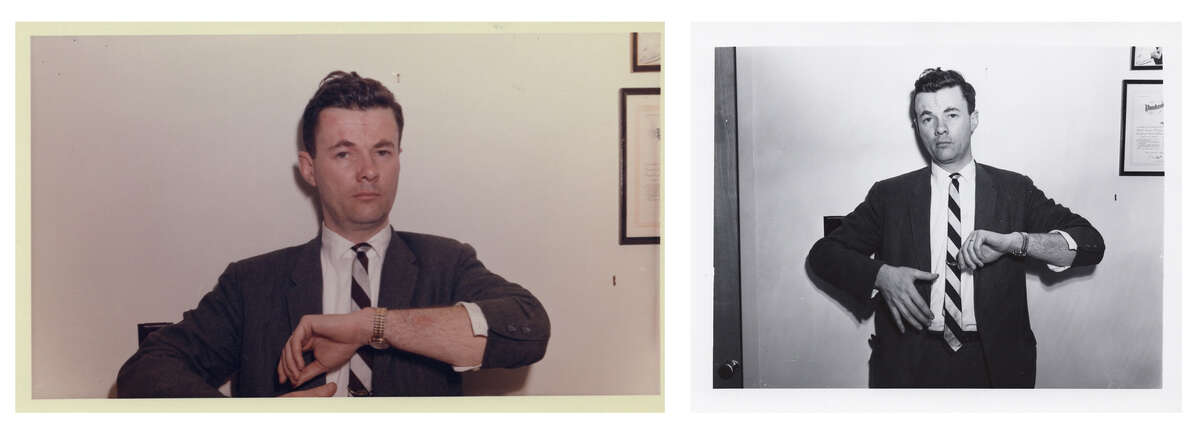

A mug shot of Cook from the FBI’s file on the Reeb murder case.

FBI file

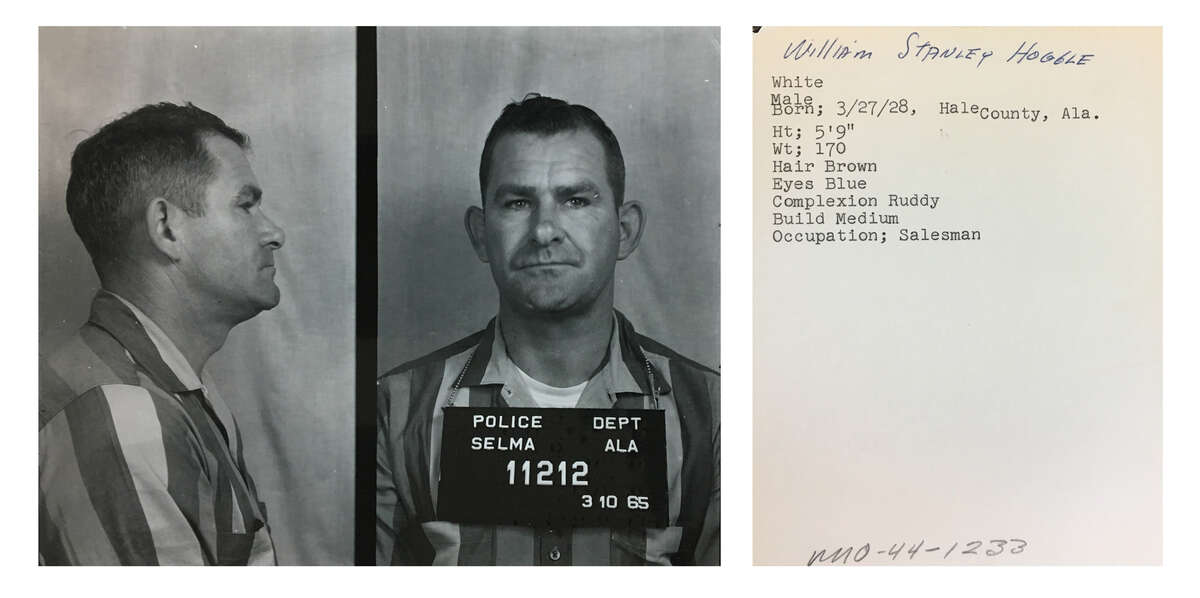

William Stanley Hoggle’s photo was also included in the FBI’s Reeb case file.

FBI file

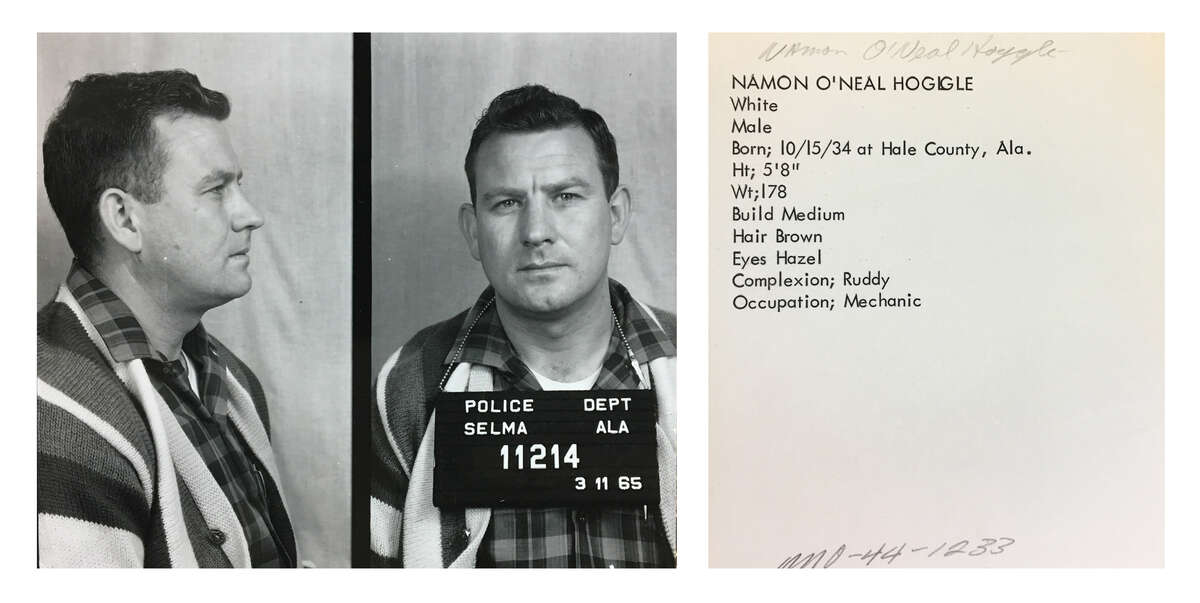

William Stanley’s brother Namon O’Neal Hoggle was also profiled in the FBI file.

FBI file

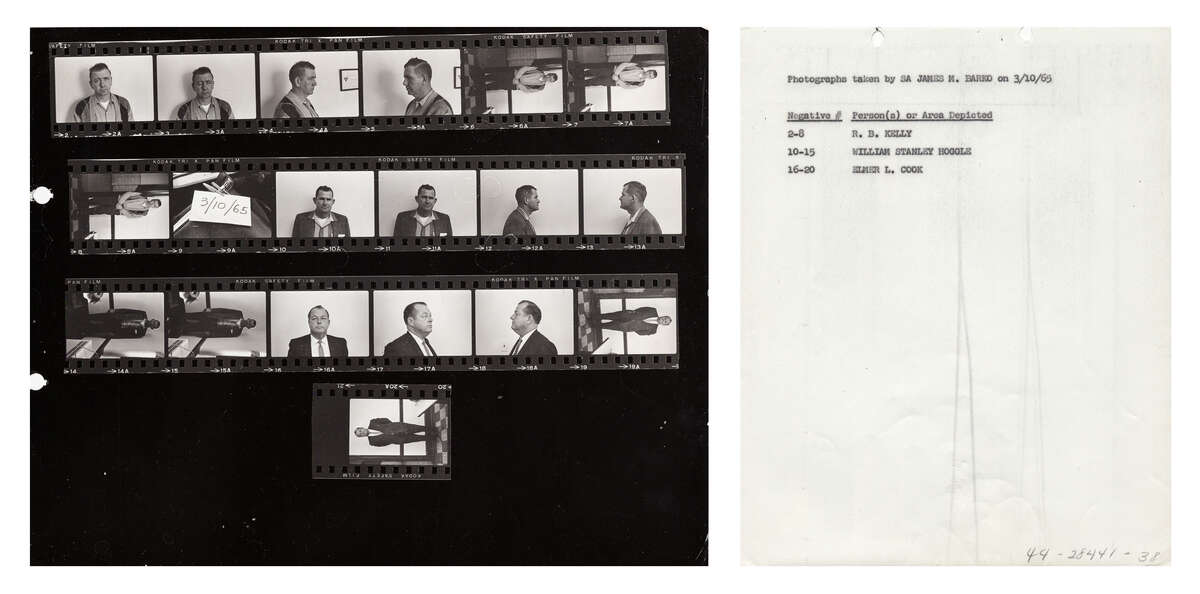

A filmstrip shows mug shots of suspects Kelly, William Stanley Hoggle and Cook.

FBI file

The Rev. Orloff Miller shows a bruise on his arm after the attack.

FBI file

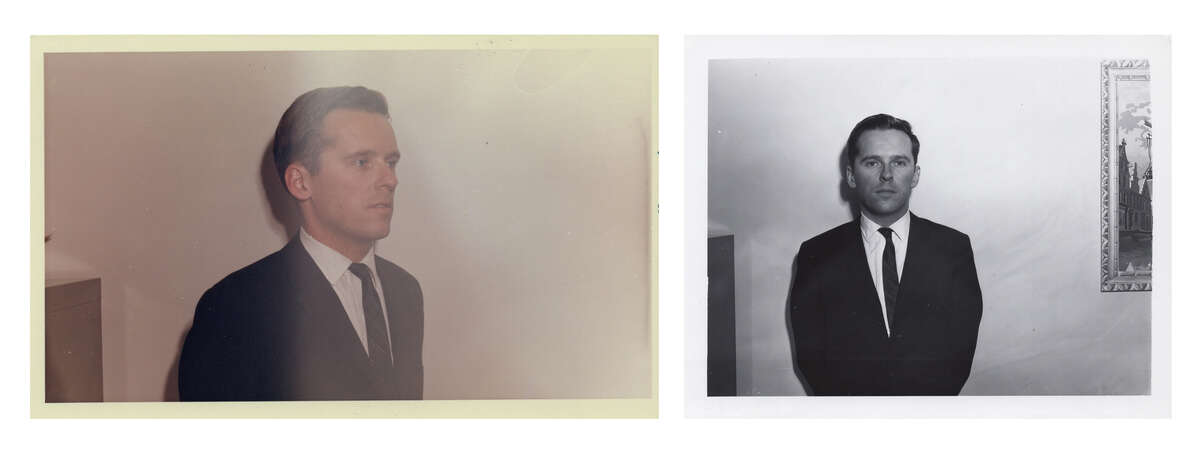

Olsen stands for a photo that the FBI collected for its file on the Reeb case.

FBI file

A monument to Nathan Bedford Forrest, one of the earliest leaders of the Ku Klux Klan, stands in Live Oak Cemetery in Selma.

William Widmer for NPR

Confederate flags mark the graves of unknown soldiers in Confederate Memorial Circle in the middle of Live Oak Cemetery.

William Widmer for NPR

Brown Chapel AME Church is across the street from the historic George Washington Carver public housing projects, a post-World War II housing development for black residents in segregated Selma.

William Widmer for NPR

A car drives past the vacant lot that was the site of the Silver Moon Cafe stood in 1965.

William Widmer for NPR

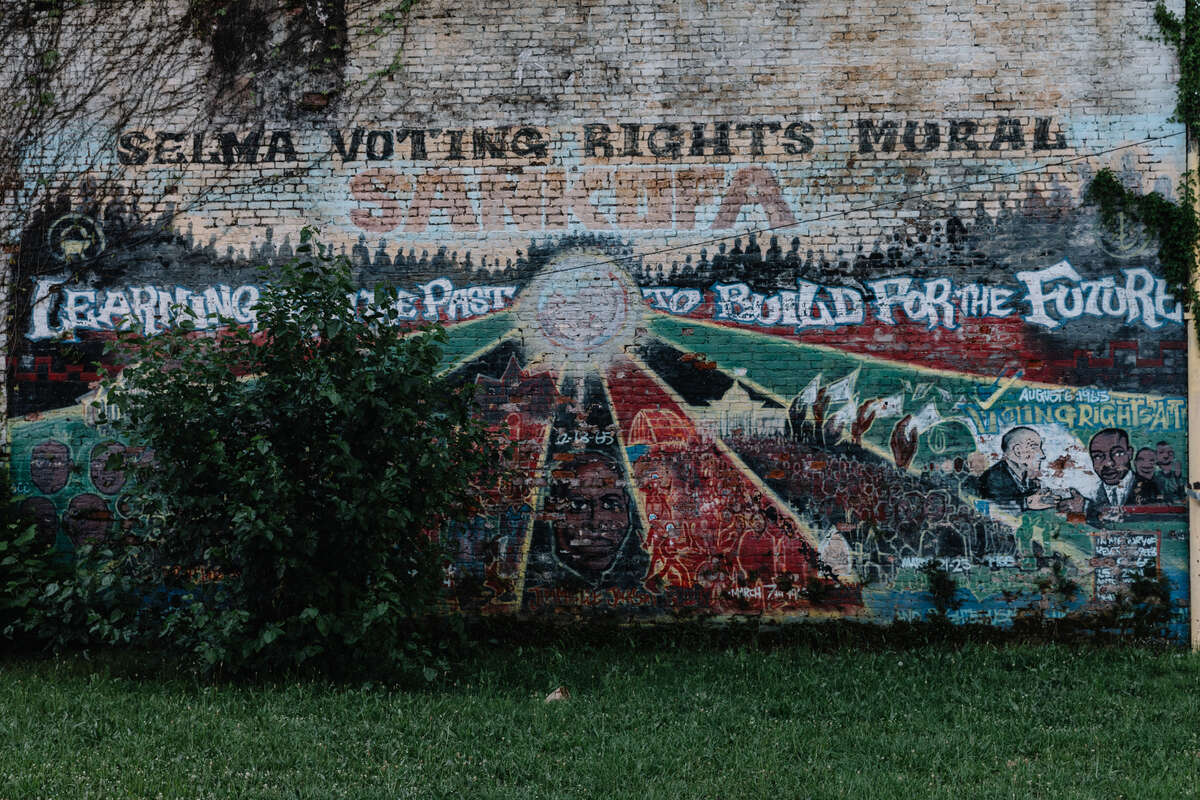

A civil rights mural, faded and covered with vines, is painted on the side of the building next to the lot where the Silver Moon Cafe once stood.

William Widmer for NPR

Tepper’s father started Tepper Bros. Mercantile Co., which evolved into Tepper’s department store. For years the store would turn its top floor into a Christmas winter wonderland for the white children of Selma. The old department store now stands empty.

William Widmer for NPR

A mural near where the Silver Moon was located depicts the "Courageous 8" — leaders of the Dallas County Voters League who helped plan and organize the 1965 Selma Campaign.

William Widmer for NPR

Traffic moves toward the Edmund Pettus Bridge in downtown Selma.

William Widmer for NPR

Many of the buildings on Water Avenue in downtown Selma are vacant.

William Widmer for NPR

Selma Bail Bond, where Bowden works, stands next to the spot where Reeb was attacked more than 50 years ago.

William Widmer for NPR

The building where Walker’s Cafe stood in 1965, now empty.

William Widmer for NPR

A memorial to Reeb was placed on the grounds of the Old Depot Museum in Selma and dedicated in November 1998.

William Widmer for NPR

Leah Reeb Varela with her father, John Reeb, and grandmother, Marie Reeb in Casper, Wyo., in May. James Reeb was Marie’s husband and John’s father.

Rachel Woolf for NPR

An Alabama state tourism plaque at the Edmund Pettus Bridge marks the location of "Bloody Sunday."

William Widmer for NPR

The Edmund Pettus Bridge crosses the Alabama River in downtown Selma.

William Widmer for NPR

A boat winds down the Alabama River.

William Widmer for NPR