I. Jury Selection

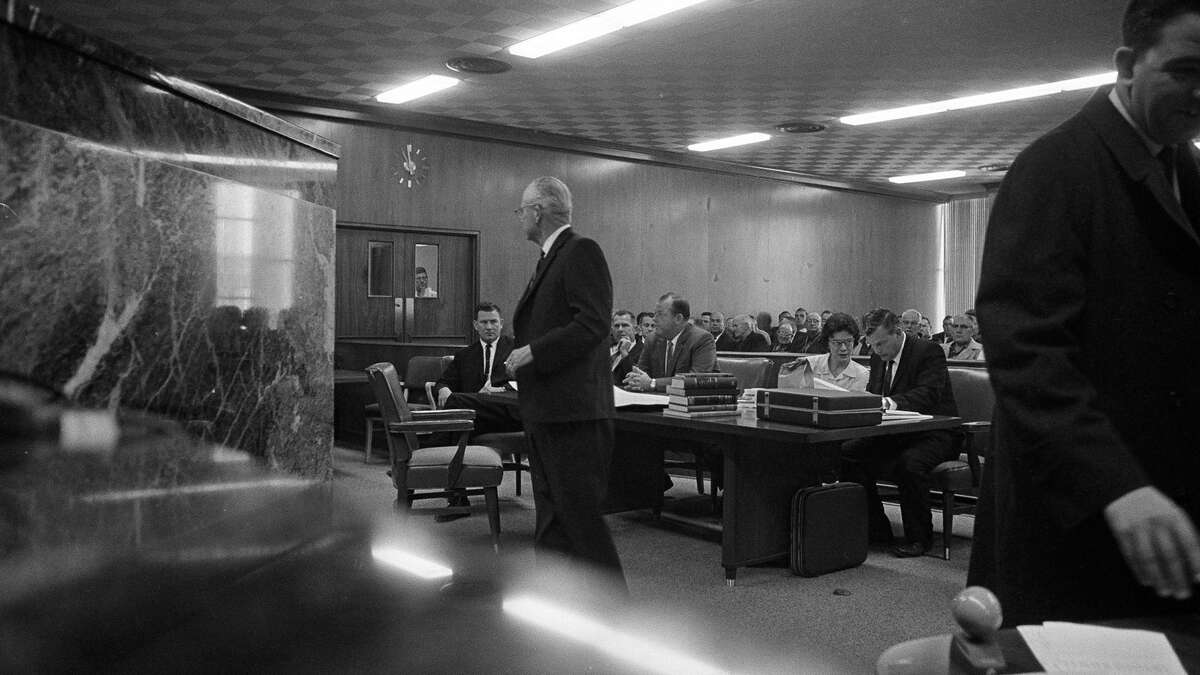

Judge L.S. Moore stands at the front of the courtroom in the Dallas County Courthouse. On the first day of the trial, Moore dismissed only one of three jurors who said the Rev. James Reeb’s civil rights work would “bias or prejudice” them in favor of the defense. Horace Cort/AP

“The 12 men who will decide the fate of three Selma men charged with murdering a Boston Unitarian minister here last spring were seated shortly after 12 noon today.” — The Selma Times-Journal, Page 1, Dec. 7, 1965

“Selecting a jury to try three white Selma residents charged with murdering a pro-integration minister here last March — could be a slow process here today.” — Jack Hopper, The Birmingham News, Page 1, Dec. 7, 1965

“It took the entire morning to swear in more than 100 witnesses and pick a jury.” — Rex Thomas, Associated Press writer, The Montgomery Advertiser, Page 2, Dec. 8, 1965

“It was a folksy trial. Ashworth and defense attorney Joe Pilcher were ‘Virgis’ and ‘Joe’ to each other. Every witness, known or unknown previously, was addressed on a first-name basis. There were Billy and Ed and Frances and Ouida — all friendly folks up there on the witness stand. Only the clergy and the doctors escaped with a ‘Mr.’ or ‘Dr.’ ” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 12, 1965

“Thirteen Negroes were on the panel of 104 prospective jurors drawn for the trial.” — Rex Thomas, Associated Press writer, The Montgomery Advertiser, Page 1, Dec. 8, 1965

“On the list from which the jury would be chosen were 107 persons, including 13 Negroes.” — The Selma Times-Journal, Page 2, Dec. 7, 1965

“[Prosecutor Blanchard McLeod] did read a temper-heating question to the 107-man venire as the jury was being selected. He took pains to make sure that all knew that the reading was under the orders of attorney general Richmond Flowers and not his idea. And then he galloped through the statement so fast that the content was elusive. ‘It asked: ‘If it should appear from evidence or testimony that the victim was friendly with, or social with, or consorted with, or treated as equals, or lived in the same quarters with Negroes, or his conduct or relations showed he considered Negroes as good as whites, or sympathized with their efforts to gain equality with whites, would such conduct or activity make the victim a low person to such an extent that it would bias or prejudice your verdict in favor of the defense?’ ” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 12, 1965

“The jurors who got the case stood mute when asked if Reeb’s civil rights activity would prevent them from reaching a fair and just verdict.” — Rex Thomas, Associated Press writer, The Montgomery Advertiser, Page 2, Dec. 8, 1965

“Only three men said they did, and Circuit Judge L.S. Moore dismissed only one of the three. … McLeod later struck the two men that Judge Moore would not excuse.” — Edward M. Rudd, The Southern Courier, Page 1, Weekend Edition, Dec. 18-19, 1965

“Two white men on the panel had spoken up angrily when Dist. Atty. Blanchard McLeod asked all of the prospective jurors at one time if any resentment they felt against civil rights workers or the belief that they were inferior would ‘make this alleged victim (Reeb) a low person to such an extent as it would bias or prejudice your verdict.” — Associated Press writer, The Birmingham Post-Herald, Page 2, Dec. 7, 1965

“Ray D. Maples, a farmer, stood and said he was afraid it might influence his verdict. ‘I’m leaning against a man who came down here from Boston,’ he said, ‘when he should have been preaching up there.’ Negroes in the audience — about 100 — murmured when W. E. Dozier, a city employee, admitted his bias, saying, ‘I feel Reeb didn’t belong down here.’ ” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 8, 1965

“One jury prospect said, ‘If a man goes in low places with them niggers, I will not say that I am on an equal basis with him, and I stand on that.’ He was not excluded, because he also said he would convict the defendants if their guilt was proved beyond a reasonable doubt. McLeod later struck the two men that Judge Moore would not excuse.” — Edward M. Rudd, The Southern Courier, Page 1, Weekend Edition, Dec. 18-19, 1965

“Smitherman said his prejudice would prevent him from reaching an impartial verdict. … Smitherman was challenged and removed from the venire but the other two remained over the prosecutors challenge.” — The Selma Times-Journal, Page 2, Dec. 7, 1965

“Richard Gibbs, W. Herbert Rose, Lamar Hubbard and James E. Godwin, J. L. Reed and Darrance Thompson … were challenged by the state because they expressed views against capital punishment and conviction on circumstantial evidence. Frank Huffman also was challenged by the state because he said he was too closely associated with two of the Hoggles to return an impartial decision.” — The Selma Times-Journal, Page 2, Dec. 7, 1965

“Named to serve on the jury were Billy G. Boozer, mail carrier, New Orrville Road; William E. Barrett, insurance agent, 2714 Water Avenue; Raymond V. Schiffer, auto service, 2312 Orrville Road; Ray Chance, former co-op, Selma; Harry C. Vardaman, automobile sales manager, 405 Battery; Willie C. Ellington, salesman, 116 Pelham; Milton L. Adams, officer electric company, 231 McDonald; T. Maynard Busby, grocery manager, 114 Bracelle Street; William W. Vaughan, on company, 2105 Church Street; M. Woods Culpepper, logger, Route 1, Selma; Cecil Campbell, listed in city directory as living at 208-C Valley Creek Homes, and J. Cooper DeRamus, 8 Buckeye Avenue.” — The Selma Times-Journal, Page 1, Dec. 7, 1965

“The jury had some interesting members. Raymond V. Schiffer, who runs an automobile parts business, openly escorted George Lincoln Rockwell, American Nazi leader, around the city on a recent visit. The foreman, William W. Vaughan, oil firm owner, resigned as a vestryman of a local Episcopal Church when it became integrated after the March protest. Harry C. Vardaman, service station owner, weighed the testimony of his brother Ben Vardaman, one of the defense’s key witnesses. And so it goes in folksy Selma.” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 12, 1965

“Court recessed for lunch immediately after the trial jury was seated.” — The Selma Times-Journal, Page 1, Dec. 7, 1965

II. Witness Testimony

The Rev. Clark Olson and the Rev. Olaf Miller leave the Dallas County Courthouse at the end of the trial’s first day. Both took the witness stand during the trial, and identified a defendant as one of their attackers. Getty Images

“The slender, dark-haired California clergyman was the first witness called to the stand in the trial.” — Associated Press writer, The Birmingham Post-Herald, Page 1, Dec. 7, 1965

“During his testimony, [Olsen] gave the following account of the attack: He, Reeb and Miller left Walker’s Restaurant, a Negro establishment, about 7:30 p.m. March 9. They started walking down the street when four or five white men started across the street towards them ‘hollering and shouting obscenities.’ ” — Jack Hopper, The Birmingham News, Page 16, Dec. 8, 1965

“Under questioning by Ashworth, Rev. Mr. Olsen … testified: ‘Four or five men came after us across the street. They shouted after us. We continued walking, going 12 or 15 feet before they reached us. One carried a stick or pipe — an object of some length.’ ” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 8, 1965

“The questioning of Olsen by Deputy Dist. Atty. Virgis Ashworth continued in these words:

Q. What did they do when they approached you?

A. Rev. Reeb was walking nearest the curb. Rev. [Orloff Miller of Boston] and I were walking on the inside. Rev. Reeb was lagging slightly behind. I looked around and saw one of the men swing the stick or club and strike Reeb on the side of the head. Miller crouched down and put his arms over [his] head.

Q. What did you do then?

A. I ran but one of the men came at me. I ran a few steps off the curb into the street but this man hit me there a few times and my glasses fell off. In a few seconds he stopped his attack on me and went away.”

— Associated Press writer, The Birmingham Post-Herald, Pages 1-2, Dec. 7, 1965

“ ‘Miller crouched down with his hand over his head to keep from being hit. I ran rather than fall to the pavement. One man came after me. I ran a few steps to the street. The man hit me there a few times and my glasses fell off. I had an especially good view of the man attacking me. I turned to face him. I raised my arms to protect myself and saw him as he hit me.’ ” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 8, 1965

“ ‘This man hit me there (in the edge of Selma Avenue) a few times and my glasses fell off,’ [Olsen] said. ‘I had a very good view of the man who was attacking me. … I turned to face him as I was running and he hit me. And I had a good view of the others.’ ” — The Selma Times-Journal, Page 2, Dec. 8, 1965

“Continuing, the witness said he looked back and ‘saw two or three men kicking Rev. Reeb and Rev. Miller while they were down. Then the men ran away.’ ” — Associated Press writer, The Birmingham Post-Herald, Page 2, Dec. 7, 1965

“Leading up to the identification Ashworth directed the questioning in these words:

Q. Could you see the men very well?

A. I had a very good view of the man who attacked me. I was facing him for a few seconds as he was hitting me. I had a fairly good view of the others.

Q. This man that hit you, do you think you could recognize him?

A. I believe I could.”

— Associated Press writer, The Birmingham Post-Herald, Pages 1-2, Dec. 7, 1965

“The minister arose. He scanned the packed courtroom. ‘Is he present?’ asked Ashworth. Silence enveloped the courtroom.” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 8, 1965

“Olsen, speaking in a crisp, clear voice … ” — Associated Press writer, The Birmingham Post-Herald, Page 1, Dec. 7, 1965

“ … pointed and said, ‘He’s next to the lady in the red dress.’ Cook returned the stare. The defendant, dressed in a neat business suit, showed no emotion.” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 8, 1965

“Cook was seated next to Pilcher’s legal secretary, who was wearing a red dress.” — Jack Hopper, The Birmingham News, Page 16, Dec. 8, 1965

“Ashworth said then, ‘I want the record to show that the defendant he pointed out is Elmer Cook.’ ” — Associated Press writer, The Birmingham Post-Herald, Page 2, Dec. 7, 1965

“Rev. Clark Olsen … startled both defense and prosecution Tuesday when he scanned 300 faces in the courtroom and then pointed his finger at Elmer L. Cook as one of his own assailants. Identification, which Rev. Mr. Olsen described as ‘positive,’ came as a surprise to the state prosecutor, who earlier had described his case as weak.” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 1, Dec. 8, 1965

“Olsen said the other two defendants seated next to Cook ‘resemble the men I remember attacking Rev. Reeb.’ But, he added, ‘I cannot positively identify them.’ ” — Associated Press writer, The Birmingham Post-Herald, Page 2, Dec. 7, 1965

“He failed to [waver] in his firm conviction that Cook was his assailant during a pressing cross examination by the defense. In later testimony he used the words ‘when Mr. Cook attacked me’ several times.” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 8, 1965

“Olsen acknowledged in response to one question that he had seen pictures of the three defendants in newspapers before FBI agents asked him to identify his attackers. Olsen denied telling policemen that night that he could not remember if the attackers were white or Negroes. He said he did not remember exactly how he described the men to investigators.” — Rex Thomas, Associated Press writer, The Montgomery Advertiser, Page 2, Dec. 8, 1965

“The court recessed at 5pm." — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 8, 1965

III. Closing Arguments

Three defendants charged with the murder of the Rev. James Reeb sit at a table with their attorney, Joseph Pilcher, during a trial recess. On the last day of the trial, Pilcher presented his closing argument: that the Civil Rights Movement let Reeb die – or killed him themselves – because it was in need of white martyr. Horace Cort/AP

“The accused men had been on trial four days.” — Associated Press writer, The Montgomery Advertiser, Page 1, Dec. 11, 1965

“Deputy DA Virgis M. Ashworth told the jury in the opening portion of his summation that he was confident the 12 men will put aside any racial prejudice.” — Associated Press writer, The Tuscaloosa News, Page 1, Dec. 10, 1965

“ ‘Whether you like him and whether you like what he was doing here, or whether you don’t,’ Ashworth said in reference to Reeb’s civil rights activity, ‘you have a duty and a responsibility. … This is your town. … We may have bitter pills to swallow, but swallow them we will because we will do our duty.’ ” — Associated Press writer, The Tuscaloosa News, Page 3, Dec. 11, 1965

“Ashworth argued, ‘The law of the State of Alabama is that if a dangerous blow is made, whoever makes that blow cannot expect medical treatment to reach down and pick him out of his guilt.’ ” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 11. 1965

“He told the jury, ‘This is an important case. It will live after you and I are gone.’ He was right. — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 12, 1965

“In his final argument to the jury, prosecutor Virgis Ashworth made it clear he was leaving the case in the jurors’ laps. ‘I feel like I did my duty,’ he told them. ‘I can go to bed tonight and sleep and not worry about this case anymore. This is your time.’ ” — Edward M. Rudd, The Southern Courier, Page 1, Weekend Edition, Dec. 18-19, 1965

“In his summation, Mr. Pilcher, the defense attorney, said Mr. Reeb was ‘knowingly and deliberately’ allowed to die by those who claimed to be seeking medical attention for him. Civil rights organizations wanted a ‘martyr,’ Mr. Pilcher said.” — Martin Waldron, The New York Times, Page 22, Dec. 11, 1965

“Pilcher argued before the case went to the jury that the ‘grossly negligent treatment’ of Reeb was an ‘adequate defense of murder. … They put this man in an ambulance like a sack of potatoes.’ ” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 11, 1965

“Defense attorney Pilcher argued that the state failed to make a case against the defendants and, ‘the pressure was on to make a quick arrest (following the Reeb slaying) and they did not investigate the facts as they should have. … Because of that,’ he declared, ‘these defendants were unfairly arrested and brought to trial.’ ” — Associated Press writer, The Montgomery Advertiser, Page 1, Dec. 11, 1965

IV. The Verdict

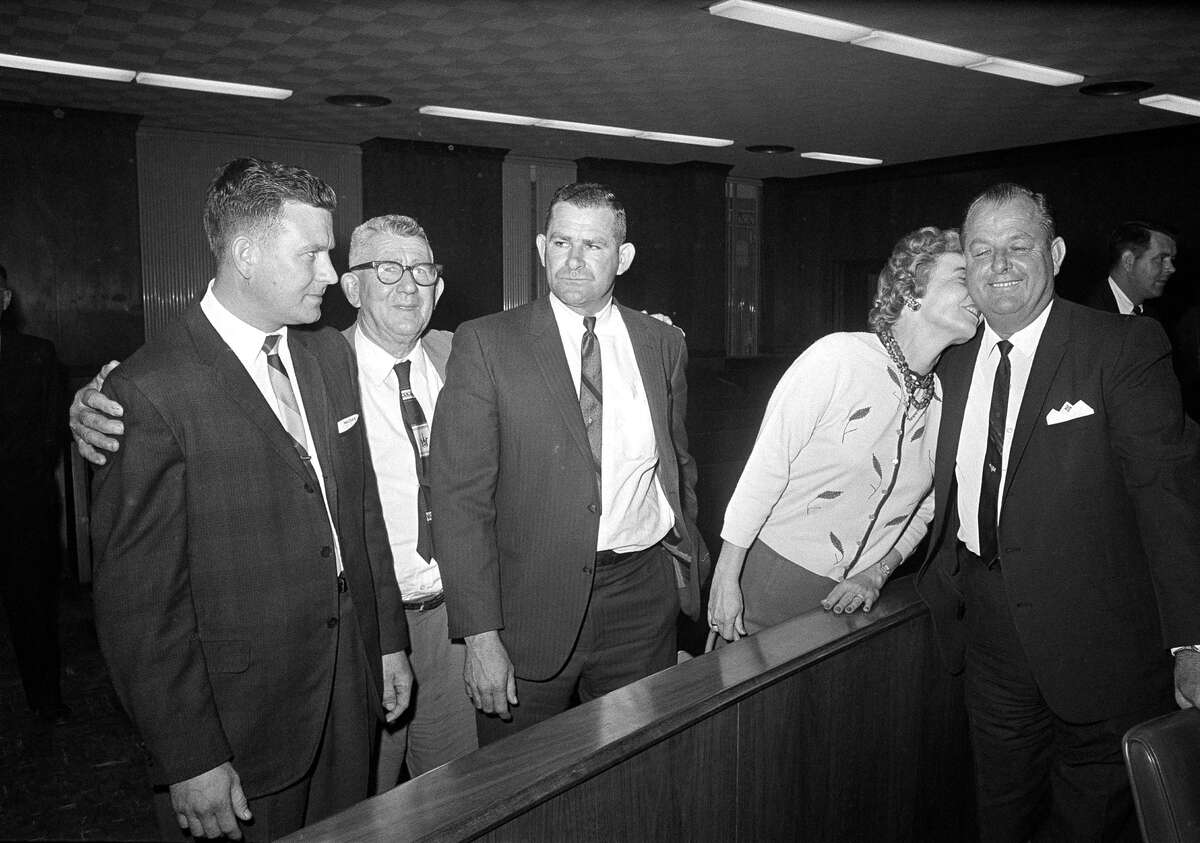

The defendants celebrate in the courtroom after they were acquitted. The Boston Globe reported that, after the verdict, “only one tear was seen in the courtroom” in the eye of the Hoggle brothers’ father, pictured here with his arms around his sons. Elmer Cook’s wife, shown kissing her husband, told The New York Times she was very happy. Horace Cort/AP

“[The] case went to the jury at 2:54 p.m. (CST).” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 11, 1965

“There was one unexplained incident in the courthouse. Sheriff Jim Clark was seen to enter the jury room at 3:58 p.m., while the jurors were deliberating.” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 1, Dec. 11, 1965

“[While] Judge L. S. Moore was charging the jury, Clark was overheard asking the bailiff for the key to the jury room.” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 1, Dec. 11, 1965

“Clark, flashing a ‘Never’ button on his lapel in response to the Civil Rights anthem ‘We Shall Overcome,’ escorted the white panel to the jury room.” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 11, 1965

“ ‘Anything you want?’ he asked as he went into the jury room and closed the door behind him. He emerged several minutes later carrying a cup of coffee.” — Martin Waldron, The New York Times, Pages 1, 22, Dec. 11, 1965

“He left the room at 4:03.” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 1, Dec. 11, 1965

“Fifteen Negroes and about 100 white spectators sat fixed in their seats, awaiting the verdict.” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 11, 1965

“At 4:30 p.m., a knock on the door of the locked jury room signaled that the verdicts were ready.” — Associated Press writer, The Montgomery Advertiser, Page 1, Dec. 11, 1965

“The ‘not guilty’ verdict came in a speedy 97 minutes. Courthouse wags claimed it would have come sooner if Sheriff Jim Clark hadn’t spilled the Cokes he was carrying to the jurors. … It came at 4:31 p.m. after Clark shouted, ‘Order in the Court.’ … ‘Have you gentlemen reached your verdict?’ Judge Moore asked after the jurors paraded back into the box.” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 12, 1965

“The hands of the white-haired jury foreman shook so badly as he read the acquittals of the three defendants that he almost tore the verdicts up.” — Edward M. Rudd, The Southern Courier, Page 1, Weekend Edition, Dec. 18-19, 1965

“As foreman Bill Vaughan sputtered out the last ‘not guilty,’ he sounded as though he were condemning the three men to die, instead of setting them free. … As Vaughan announced the not-guilty verdicts, he and the other 11 white men on the jury hung their heads. They seemed to know they had been on trial for four days along with the defendants.” — Edward M. Rudd, The Southern Courier, Page 1, Weekend Edition, Dec. 18-19, 1965

“The acquittal also cleared the three defendants of three lesser charges — second-degree murder and first-degree and second-degree manslaughter.” — Martin Waldron, The New York Times, Page 1, Dec. 11, 1965

“The white spectators burst into applause. Negroes in a body groaned, rose in their seats and broke for the doors.” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 11, 1965

“Circuit Judge L. S.Moore told the crowd to ‘sit down!’ ” — Rex Thomas, Associated Press writer, The Atlanta Constitution, Page 1, Dec. 11, 1965

“An estimated 100 white spectators in the courtroom, most of whom were family and close friends of the defendants, applauded the decision. A Negro woman appeared to express the reaction of her race when she grumbled: ‘I knowed they wasn’t going to do nothing.’ ” — The Selma Times-Journal, Page 1, Dec. 12, 1965

“A group of Negroes attempted to leave the courtroom while the verdicts were being read by the jury foreman, William [Vaughan]. They were ordered back to their seats by Sheriff Clark." — Martin Waldron, The New York Times, Page 1, Dec. 11, 1965

“Clark shouted and dashed toward them with his two deputies. ‘Order in the court. Order in the court,’ he yelled. ‘Get back to your seats.’ They returned to the benches.” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 11, 1965

“Glancing then over the three sheets of paper handed to him by the jury foreman, the judge said, ‘The jury’s verdicts are in order. The defendants are discharged. Court is adjourned.’ ” — Rex Thomas, Associated Press writer, The Atlanta Constitution, Page 1, Dec. 11, 1965

“The defendants — Elmer L. Cook, 42, manager of a novelty company; Namon O’Neal Hoggle, 31, an auto mechanic, and his brother, William Stanley Hoggle, 37, a salesman — displayed no emotion.” — Rex Thomas, Associated Press writer, The Atlanta Constitution, Page 1, Dec. 11, 1965

“Asst. Solicitor Virgis M. Ashworth, prosecutor, and Defense Atty. Joe T. Pilcher shook hands warmly before the jury box.” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 11, 1965

“Spectators in the crowded wood-paneled courtroom clapped hands and shouted when the trial jury returned the three verdicts — one for each defendant. … They posed for photographers inside the courtroom after shaking hands with well-wishers who swarmed about them.” — Associated Press writer, The Tuscaloosa News, Page 1, Dec. 11, 1965

“Cook put his arm around his blonde wife to have their picture made.” — Associated Press writer, The Montgomery Advertiser, Page 1, Dec. 11, 1965

“Mrs. Cook said she was very happy.” — Martin Waldron, The New York Times, Pages 1, 22, Dec. 11, 1965

“Only one tear was seen in the courtroom. It was in the eye of the Hoggle brothers’ elderly father. He threw his arms around William Stanley and kissed him.” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 11, 1965

“Shaking hands with Cook, defense attorney Joseph T. Pilcher said, ‘I am glad it worked out all right.’ He asked his clients not to make any statements.” — Rex Thomas, The Atlanta Constitution, Page 1, Dec. 11, 1965

“At the suggestion of defense attorney Joseph T. Pilcher, the jubilant defendants stood silent when newsmen asked them for comment.” — Associated Press writer, The Tuscaloosa News, Page 1, Dec. 11, 1965

“William Stanley Hoggle … would express no reaction, and when his father was asked to comment he advised him, ‘Don’t tell ‘em nothing, Pa.’ ” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 11, 1965

“ ‘I was quite pleased with the verdict, of course,’ Pilcher said. ‘But it was not unexpected. It was the only verdict which would have been consistent with the evidence.’ ” — Associated Press writer, The Montgomery Advertiser, Page 1, Dec. 11, 1965

“Deputy Dist. Atty. Virgis M. Ashworth, who handled the prosecution, said he did not as a rule comment on verdicts. ‘I try these criminal cases and do the best I can,’ he said. ‘Then it’s up to the jury.’ ” — Associated Press writer, The Montgomery Advertiser, Page 1, Dec. 11, 1965

“Virgis Ashworth, who handled the prosecution, said he was not surprised at the verdict.” — Martin Waldron, The New York Times, Page 22, Dec. 11, 1965

“Dist. Atty. Blanchard McLeod, who had said when the trial started that he had a weak case, declined comment.” — Associated Press writer, The Montgomery Advertiser, Page 1, Dec. 11, 1965

“Spectators and defendants faded from the vicinity of the green Dallas County courthouse, and Selma was a quiet city.” — Edward G. McGrath, The Boston Globe, Page 2, Dec. 11, 1965