Veriko Ekhvaia is wrapping up her shift at Radio Atinati, a community radio station in Zugdidi. The 29-year-old DJ gathers up the loose papers that have scattered across the desk and double-checks that the microphone is off before walking out of the studio. It’s a Sunday afternoon, not her usual weekend morning shift hosting a music show, but someone called in sick and Ekhvaia is not one to say no to a little extra work.

“Being an IDP shouldn't be a reason to be stuck in the past and always crying over what you have lost,” she says. “I still believe it's possible to work hard and change your life for the better.”

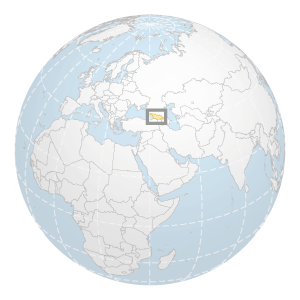

Ekhvaia has done just that. Her family, repeatedly uprooted after the western region of Abkhazia declared independence in 1993, made sure she got a good education. And these days, she is busy; her DJ job is one of three. She also works as a full-time economist for a Georgian business development program and is a part-time English tutor. Like many in the younger generation of IDPs, Ekhvaia sees herself as no different from her peers who had more stable upbringings.

When she started working at Radio Atinati in 2010, she had just graduated from college with an economics degree and was trying to find work as a bank teller or an accountant. When that didn’t happen, she applied for the DJ position as a stopgap. Radio Atinati broadcasts across the region, including in Abkhazia, and seven years later, Ekhvaia still delights in the knowledge that people from the village where she was born can tune in and hear her voice.

That village, Nabakevi, is just 8 miles away from Zugdidi, but it sits across the disputed border dividing Georgia and Abkhazia in territory controlled now by the Russian-backed Abkhaz government.