Around 2015, North Atlantic right whales began disappearing from the waters where they spend summers feeding.

Some began swimming hundreds of miles farther north to find food.

With only about 340 left, right whales are highly endangered. The journey is putting them in new peril.

Two thousand miles away, the world’s second-largest ice mass is melting.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Greenland’s ice is up to 2 miles thick, but as the climate gets hotter, it’s beginning to shrink.

Scientists are racing to measure how rapidly that melt is speeding up.

Now, scientists are finding what happens on Greenland could be linked to the future of right whales.

The planet’s rapidly melting ice is having surprising and far-reaching effects.

Sea change: How melting ice is disrupting the world’s oceans

Climate change is pushing already imperiled whales to the brink, a sign of deeper shifts in the oceans as the world’s ice melts.

Reporting by Lauren Sommer and Ryan Kellman

On a warm summer day, the surface of Greenland is alive.

Meltwater flows and begins to pool, forming rushing rivers on top of the ice.

A research team from the University of Sheffield is studying how this water could accelerate Greenland’s melt.

At three times the size of Texas, the massive ice sheet holds roughly 8% of the world’s fresh water.

Since 2002, Greenland’s ice sheet has been losing 280 billion tons of ice per year.

The question now is how rapidly will that grow as global temperatures keep rising?

But predicting how ice will melt is no simple task. To do that, scientists need to know what’s happening under the ice.

To follow the meltwater on its journey, the scientific research team releases a nontoxic fluorescent dye into the river.

The river pours into an opening in the ice, cascading like a waterfall. At the bottom, it keeps going, flowing underneath the ice sheet itself.

The warm meltwater eats away at the ice from below.

It also makes the massive ice sheet more slippery at certain times of year, speeding up its gradual flow toward the ocean.

Because eventually, Greenland’s ice will reach the Atlantic Ocean in the form of water.

That’s where it’s setting off a cascade of global consequences.

Greenland sits at the crux of a powerful ocean current in the Atlantic, one that’s vital to the circulation of heat around the planet.

It’s known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC.

Here’s how the current flows.

Vast amounts of warm water, heated near the equator, are carried up the East Coast of the U.S.

When it reaches Greenland, the water cools off, releasing its heat into the atmosphere.

The cold, salty water is now heavy. It sinks to the bottom of the ocean and starts flowing back south, deep below the surface.

Scientists call it the ocean’s great “conveyor belt.” The sinking is the engine that helps power the entire current.

But as Greenland melts, fresh water is pouring into the Atlantic Ocean. Fresh water is lighter than salty water and doesn’t sink as readily.

That could slow down the entire current by handicapping its engine.

Studies show that the more Greenland melts, the more the Atlantic current could weaken.

Measurements in the ocean show that could already be happening, but some scientists say it needs to be studied longer to say for sure.

One part of the current is already changing.

Off the coast of New England, a shift in the current is pushing warm water closer to the coast of Maine.

As a result, waters in the Gulf of Maine are heating up faster than 97% of the global ocean.

Sea surface temperature change

Colors show the difference between temperatures in August 2022, compared with the historical average from 1985-1993.

-5

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

+1

+2

+3

+4

+5

+6

+7

+8° C

That’s a problem for endangered right whales.

They typically migrate there to feed during the summer. But now the whales are no longer appearing.

Gregory Rec/Portland Press Herald via Getty Images

Gregory Rec/Portland Press Herald via Getty Images

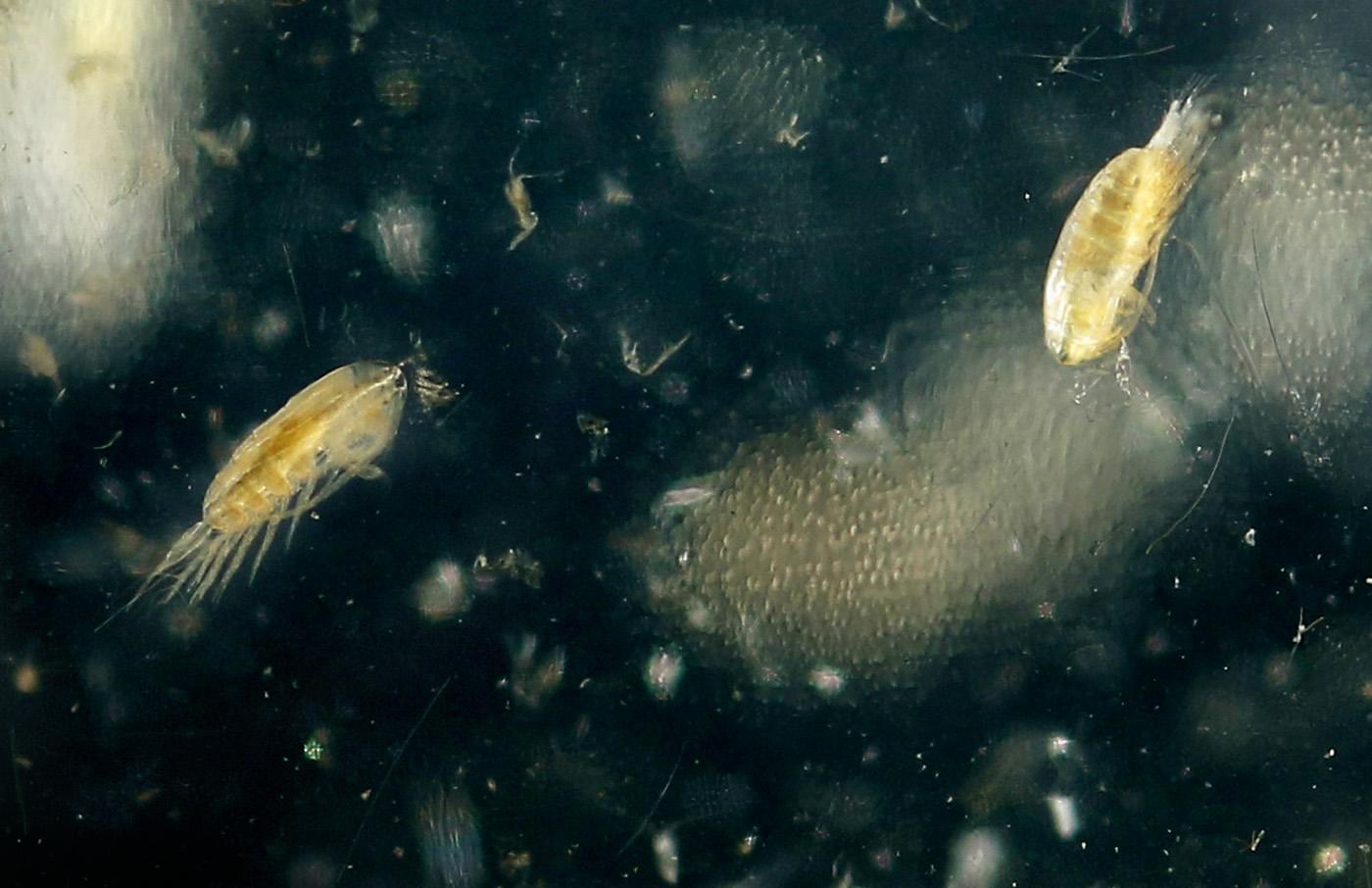

That’s because their main food supply, an organism the size of a grain of rice called Calanus finmarchicus, has decreased in the Gulf of Maine. It only survives in colder waters.

About 40% of the right whales have followed their food north, swimming hundreds of miles farther to the Gulf of St. Lawrence in Canada. The rest are still unaccounted for during the summer.

That journey has put them in the path of new dangers.

Right whales already risk injury on their migration route, either by being struck by ships or tangled in long ropes from fishing gear.

About 85% of whales show the scars of being previously entangled.

Nathan Klima for The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Nathan Klima for The Boston Globe via Getty Images

When the whales appeared in new locations, there were no protections in place.

In 2019, a young whale known as Wolverine was found dead, floating in Canadian waters.

He was one of 21 whales that died there between 2017 and 2019. Many were struck by ships or entangled.

New England Aquarium under DFO Canada SARA permit

New England Aquarium under DFO Canada SARA permit

“There’s such a small number of animals left. Some of them we have histories of great-grandmothers, grandfathers, cousins and we see how each one of them has been impacted. The tragedy of it all feels more personal.”

— Philip Hamilton, senior scientist at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium

Since then, the Canadian government has added some safeguards, like closing fishing grounds when whales are in the area. Speed limits for ships, meant to prevent deadly collisions, have also been put in place, but are only optional in some areas.

Gina Lonati/University of New Brunswick

Gina Lonati/University of New Brunswick

But as the climate keeps changing, the whales may need to move again to unexpected places.

It’s not just whales at risk. Biologists say their shift is an early signal that entire ecosystems could relocate or disappear if ocean currents change.

“We’re entering this time of extreme uncertainty. We can’t look at the past and let that shape the future because humans have thrown a wrench in what used to be natural processes.”

— Erin Meyer-Gutbrod, ecologist at the University of South Carolina

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

The key to protecting the whales and other marine life could be anticipating where they’ll go, so protections and conservation measures can be put in place ahead of time.

That depends on understanding the dynamics of the Atlantic Ocean, its fluctuating currents and the connection to a massive ice sheet sitting on top of Greenland.