More than 25 million acres have burned in the Western U.S. since 2018. Some fires have been so extreme, they’ve seemed impossible to contain.

Josh Edelson/AFP via Getty Images

Josh Edelson/AFP via Getty Images

Weather has been the deciding factor in many of those fires.

When hot, arid conditions settle on the Western U.S., the fire danger skyrockets.

Nathan Kurtz/NASA

Nathan Kurtz/NASA

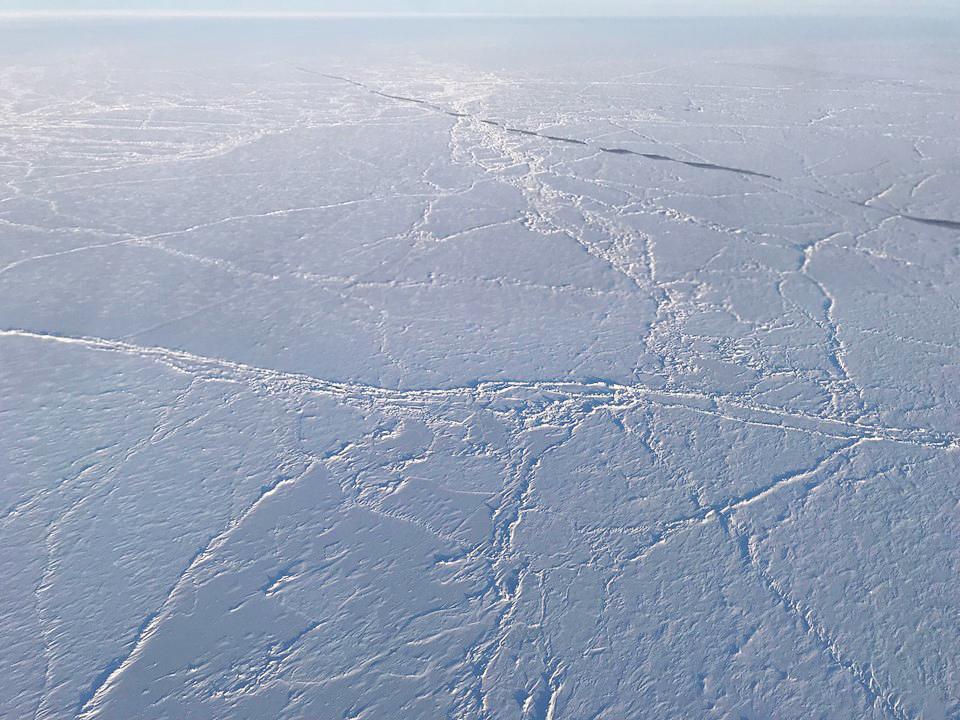

Far to the north, the season of ice is changing.

The Arctic Ocean is normally covered in a vast, frozen blanket for most of the year.

Kathryn Hansen/NASA

Kathryn Hansen/NASA

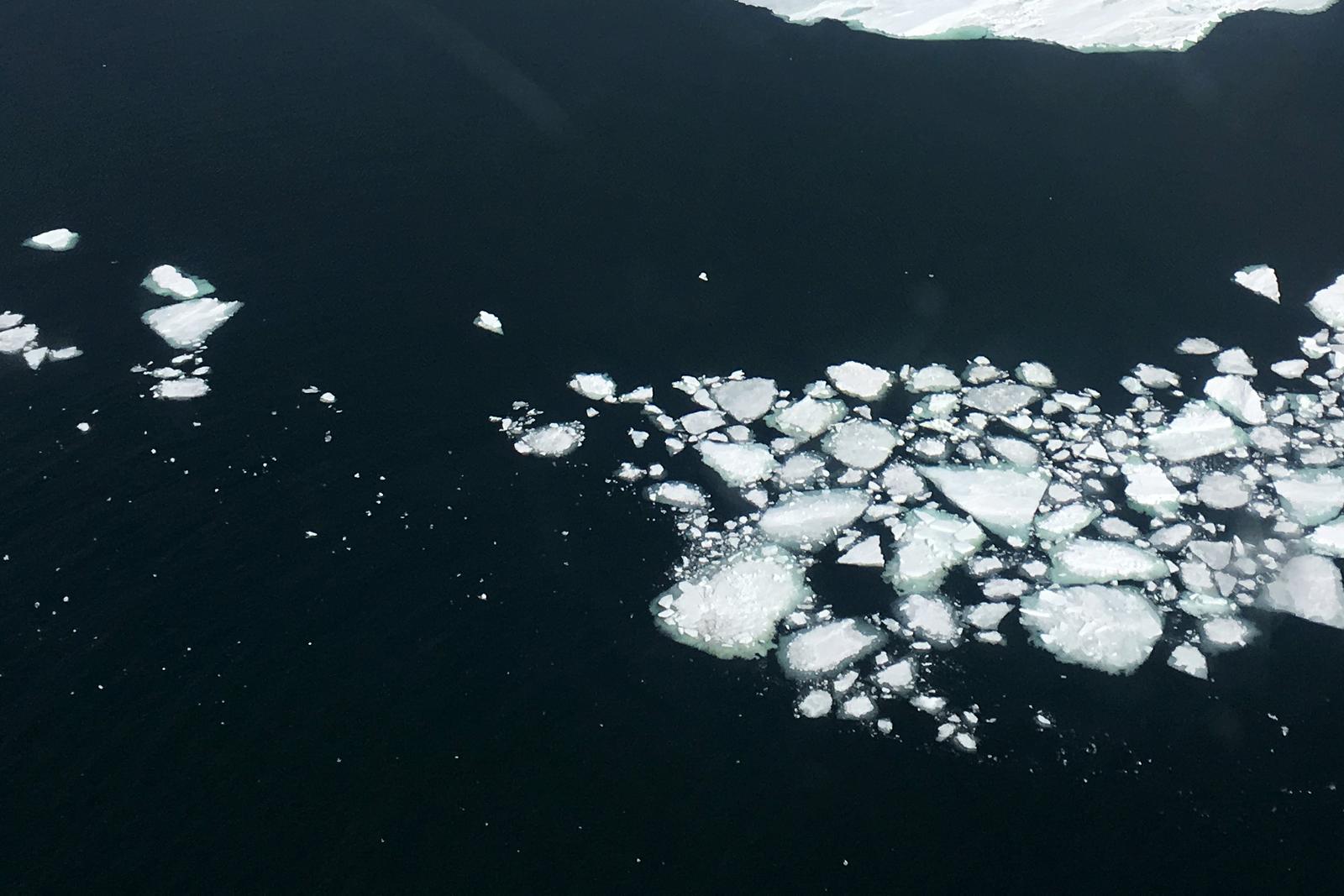

But sea ice is shrinking. It’s breaking up earlier in the spring and forming later in the fall.

As the climate gets hotter, the Arctic is spending more days as open ocean.

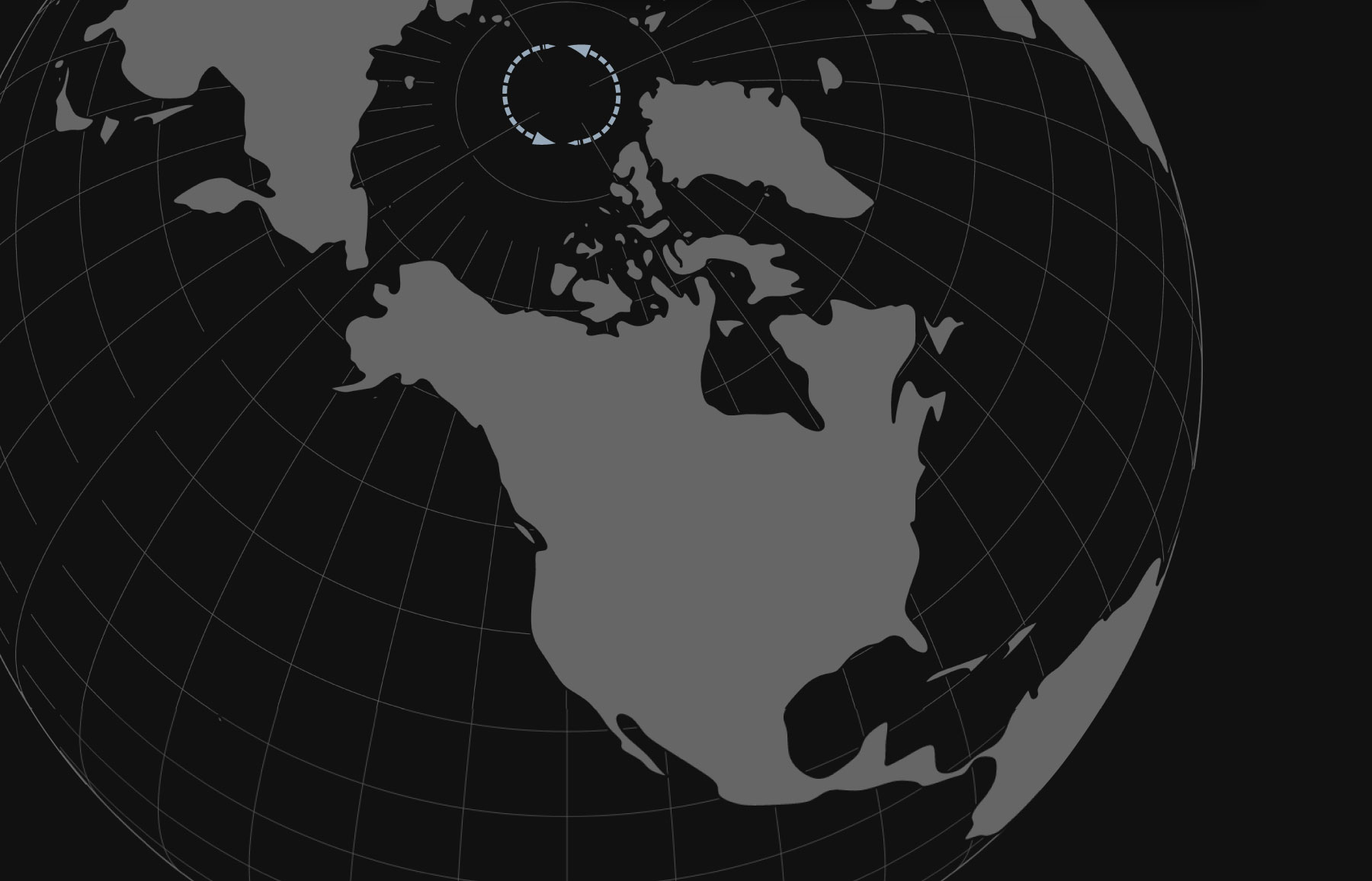

These extremes of fire and ice are more than 3,000 miles apart.

But now, connections are emerging.

Fire and Ice

The planet’s ice is fundamentally tethered to weather patterns that stretch across the globe. Scientists are finding that as the climate changes, that connection could be helping fuel disasters.

Reporting by Lauren Sommer and Ryan Kellman

It’s a warm afternoon in early July in the village of Kotzebue, Alaska, 33 miles above the Arctic Circle.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Open water is becoming an increasingly common sight this time of year.

Jessie Lindsay

Jessie Lindsay

In decades past, ice would still be floating by the shoreline, left over from the long winter months when it covers the ocean, stretching across the horizon.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

The community is feeling the fallout of a rapidly warming climate.

The changes on their doorstep are a bellwether for larger impacts to come.

David Ducoin/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

David Ducoin/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Ice is a way of life for the Iñupiat, who have lived here for thousands of years.

There are no roads in or out of town. Sea ice is a vital pathway for travel to nearby communities and for finding and gathering food.

Most residents depend on subsistence hunting for their traditional foods, including fish, seals and caribou, as has been done for generations.

Jessie Lindsay/NMFS MMPA Permit No.19309

Jessie Lindsay/NMFS MMPA Permit No.19309

Bearded seals, or ugruk, are an important food source. In the spring, the seals arrive as the ice starts to break apart and stay only a short time until the ice disappears.

Jesse Lindsay/NMFS MMPA Permit No. 19309

Jesse Lindsay/NMFS MMPA Permit No. 19309

That season is getting even shorter now. In some years, it has become too brief for hunting to be successful. Traveling across thinning ice is more precarious.

Andy Mahoney/University of Alaska Fairbanks

Andy Mahoney/University of Alaska Fairbanks

To study this shift, village elders worked with scientists at Columbia University and the University of Alaska Fairbanks to combine traditional Indigenous knowledge with scientific measurements.

Josh Cargle/EyeEm via Getty Images

Josh Cargle/EyeEm via Getty Images

They found that the sea ice is breaking up three weeks earlier now on average than it did in 2003.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Village elders like Cyrus Harris say the signs are undeniable.

“Our colder temperatures throughout the winter are no longer colder temperatures,” he says. “Earlier spring thaws — it’s obvious. Later fall freeze-up — it’s obvious.”

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

“It’s going to be a big challenge for the younger generation. It’s not a good sight for me to be envisioning,” Harris says.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

And what happens in the Arctic radiates far beyond its borders.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

“The Arctic only works when it’s cold, and it’s the air conditioner for the planet.

“So as the Arctic breaks down, the climate connections of the whole planet break down.”

— Alex Whiting, environmental director for the Native Village of Kotzebue

The Arctic is heating up more than twice as fast as the rest of the planet.

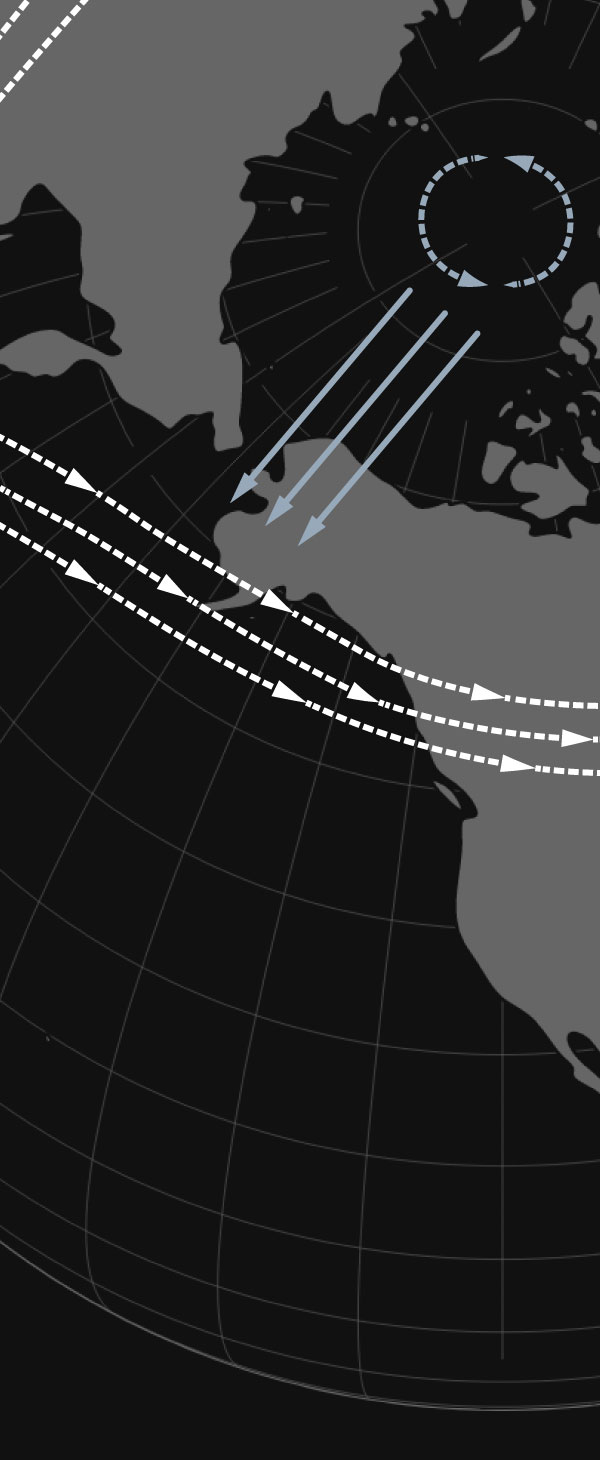

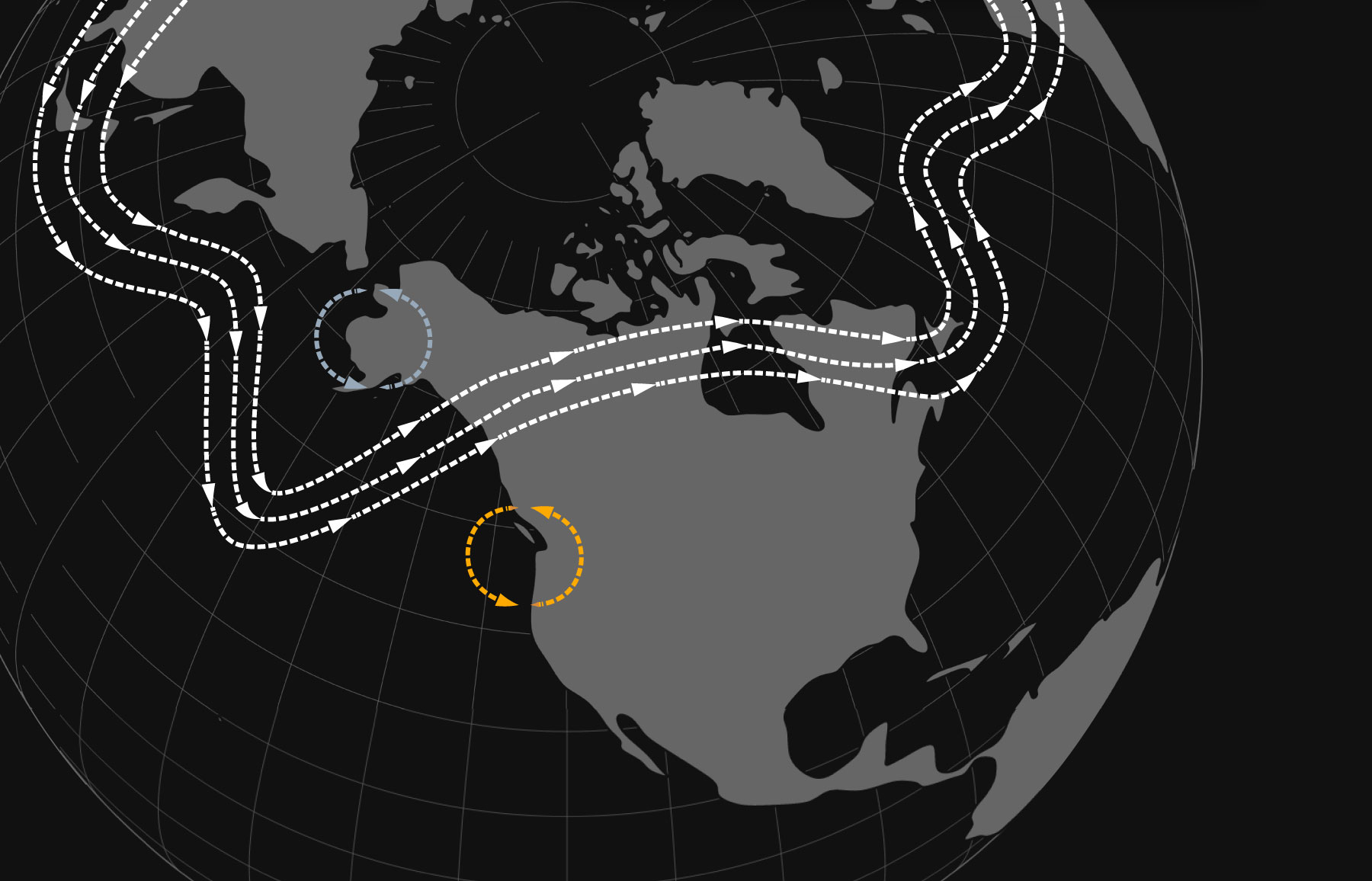

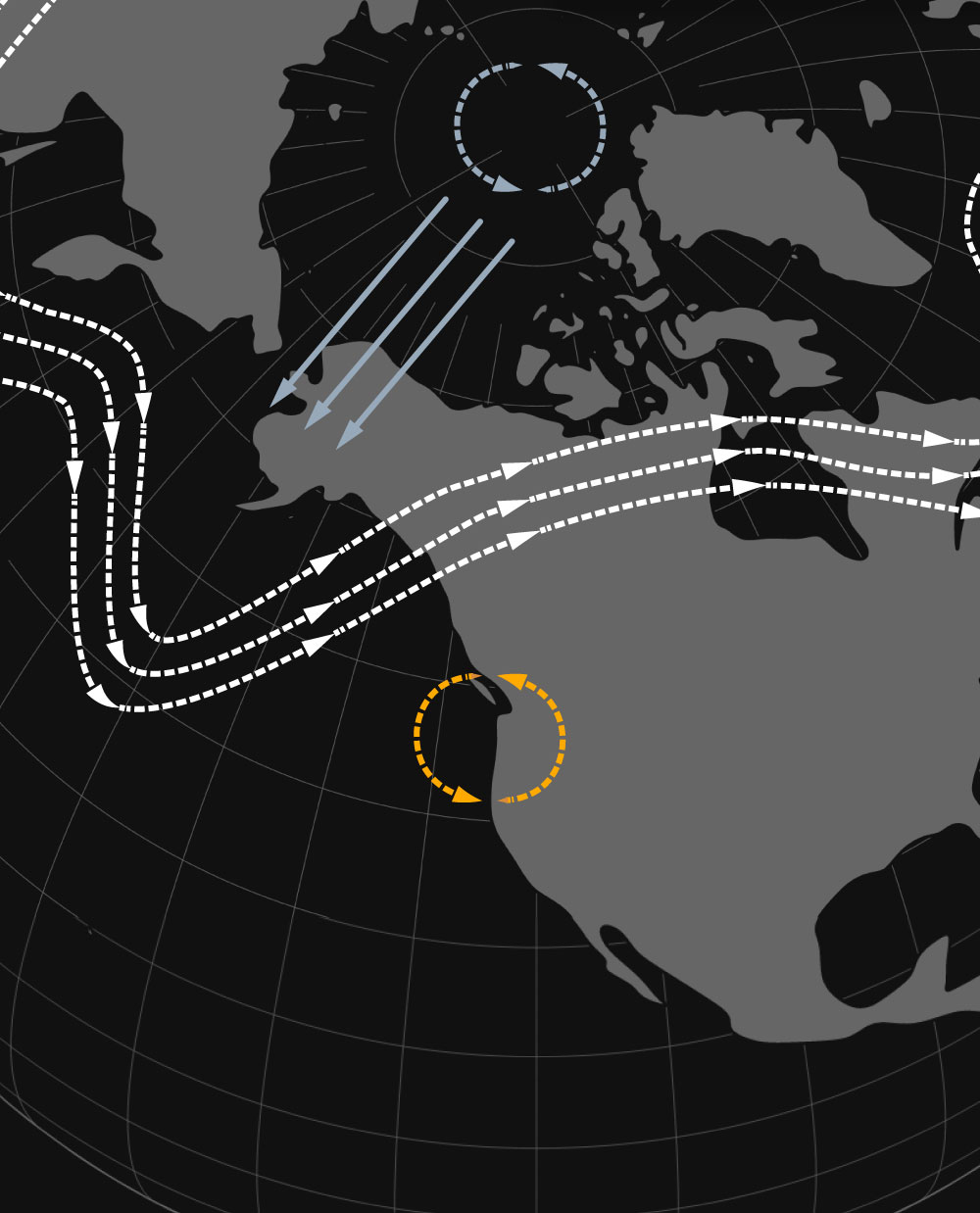

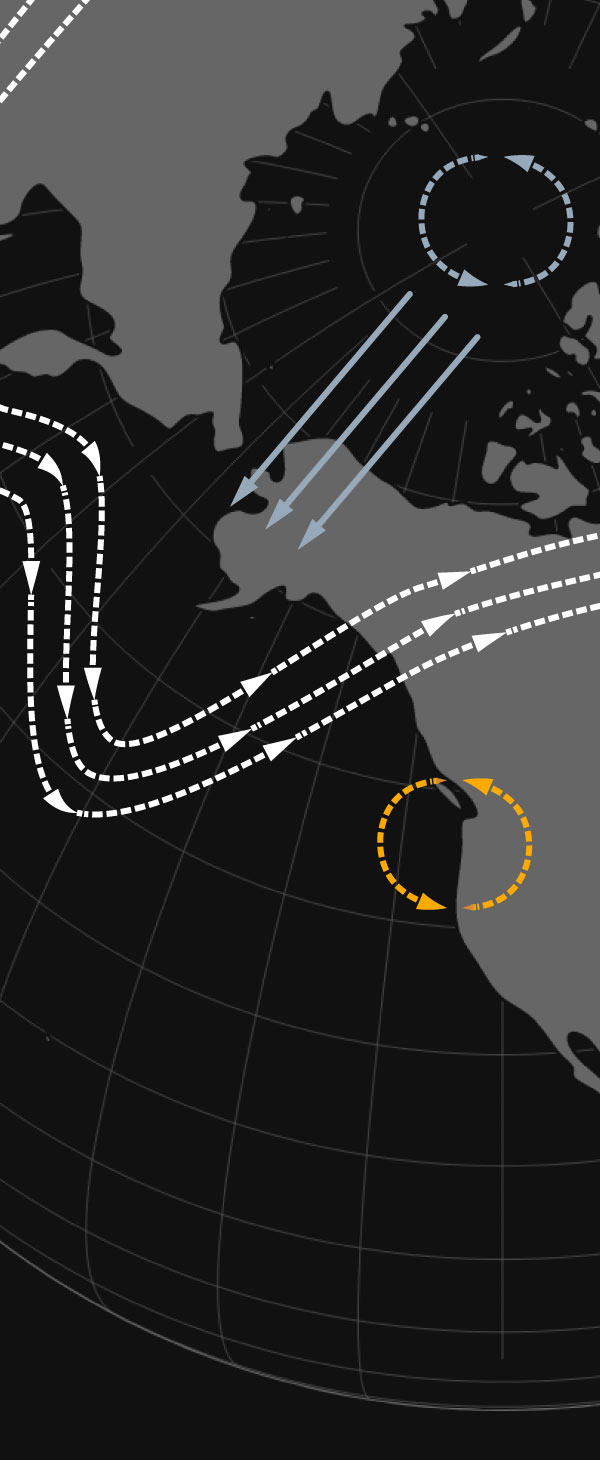

This animation shows the amount of ice in the Arctic Ocean at the end of summer from 1979-2022. It has been shrinking by 13% each decade.

Connie Hanzhang Jin/NPR

Connie Hanzhang Jin/NPR

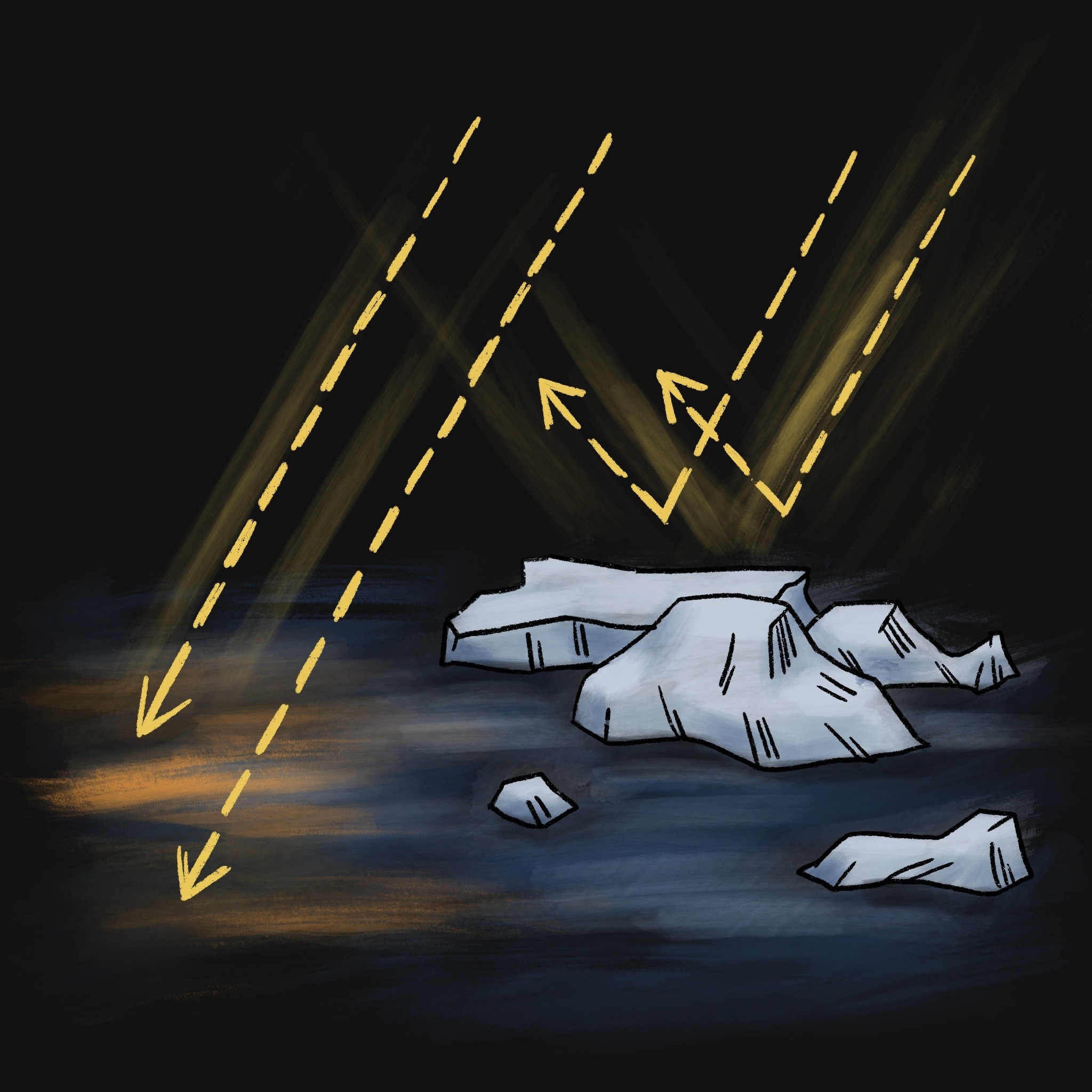

Bright white ice is really good at reflecting sunlight.

But with less ice cover, that sunlight is hitting the ocean, heating up the water.

Connie Hanzhang Jin/NPR

Connie Hanzhang Jin/NPR

That hotter water releases its heat into the atmosphere, and the warm air rises.

Low

ALASKA

Low

ALASKA

Low

ALASKA

It creates a spinning mass of air known as a low-pressure system.

Low

Jet stream

Low

Jet stream

Low

Jet stream

It’s so strong, it can influence the polar jet stream, the powerful band of winds that steers weather patterns across the U.S.

Low

Jet stream

Low

Jet stream

Low

Jet stream

The low-pressure system pushes the jet stream off its usual course, causing it to dip.

Low

Jet stream

High

Low

Jet stream

High

Low

Jet stream

High

As a result, a zone of hot, dry air known as a high-pressure system can be strengthened.

Research shows that as Arctic sea ice declines, this phenomenon could become more common in the fall.

It’s a season when, in the Western U.S., arid weather can have disastrous consequences.

Kent Nishimura/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Kent Nishimura/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

In late September 2020, firefighter Mark Macias and his crew were called to a wildfire in a rural part of Napa County, Calif.

They were the first on the scene and knew immediately the situation was dire.

Noah Berger/AP

Noah Berger/AP

Hot, arid weather was expected for days, due to a high-pressure system over California.

The critically dry air sapped vegetation of its moisture, priming it to burn.

The fire exploded, spreading hundreds of acres in the first day.

Macias and his team worked more than 50 hours straight, evacuating residents from neighborhoods with narrow, winding roads.

Lauren Sommer/NPR

Lauren Sommer/NPR

“Fire of this magnitude, the size, how fast it moves … you can’t get in front of it.

“You try to do a lot, but it feels like you can’t win.”

— Mark Macias, St. Helena Fire Department

Noah Berger/AP

Noah Berger/AP

More than 1,500 homes and buildings were lost in the Glass Fire.

It’s just one of many Western wildfires in recent years where extreme weather has driven explosive fire behavior.

Sam Hall/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Sam Hall/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Scientists are working to better understand how these dangerous conditions are linked to what happens in the Arctic and the role that it plays in weather shifts worldwide.

The hope is that Western states could get an early warning when a fire season may be particularly risky. That means closely tracking the rapidly shrinking ocean of ice thousands of miles away. On a hotter planet changing in unexpected ways, what’s distant is becoming local.

“The change in the Arctic could affect anywhere people live. If you live on the same Earth, you will feel the change.”

— Hailong Wang, Earth scientist at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory