There are no roads here. No cars.

There is only the trail.

And it is as busy as a highway.

Blankets, lumber, eggs and beer are carried up.

Cheese, milk, grain and wool are carried down.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

The supplies support shops, hotels …

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

… monasteries, farms and schools in half a dozen communities.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Hundreds of people call this place home.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

The roar of the Rolwaling River is so constant and predictable that it fades into the background of daily life.

But the river is changing.

It has gone from predictable to life-threatening.

And the reason lies at the top of the valley, where the river is born and a glacier is dying.

The Meltdown

Melting glaciers are leaving behind large, unstable lakes around the world.

Millions of people live downstream, in places increasingly threatened by deadly flash floods.

What will it take to protect them?

Reporting by Rebecca Hersher, Ryan Kellman and Pragati Shahi

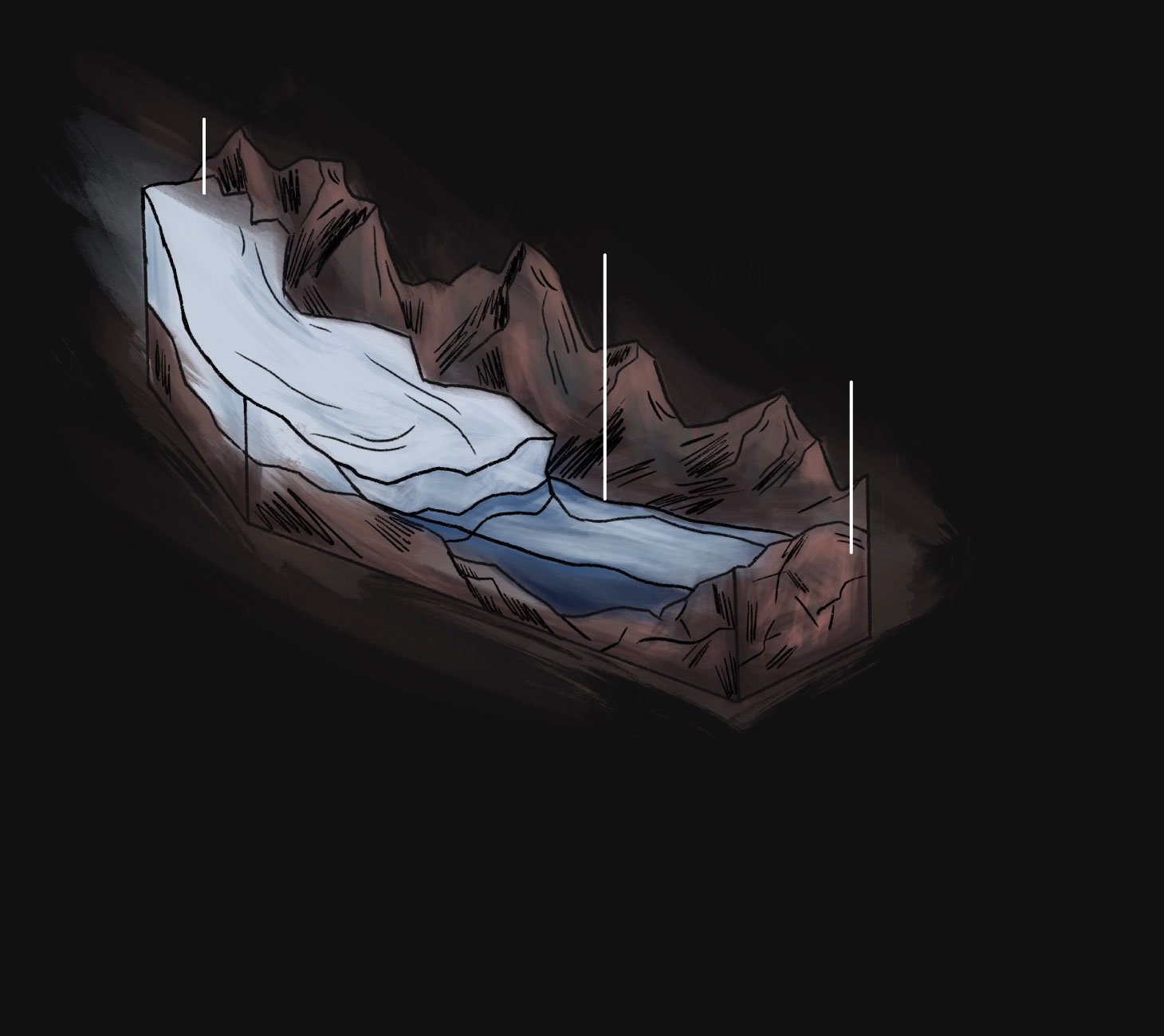

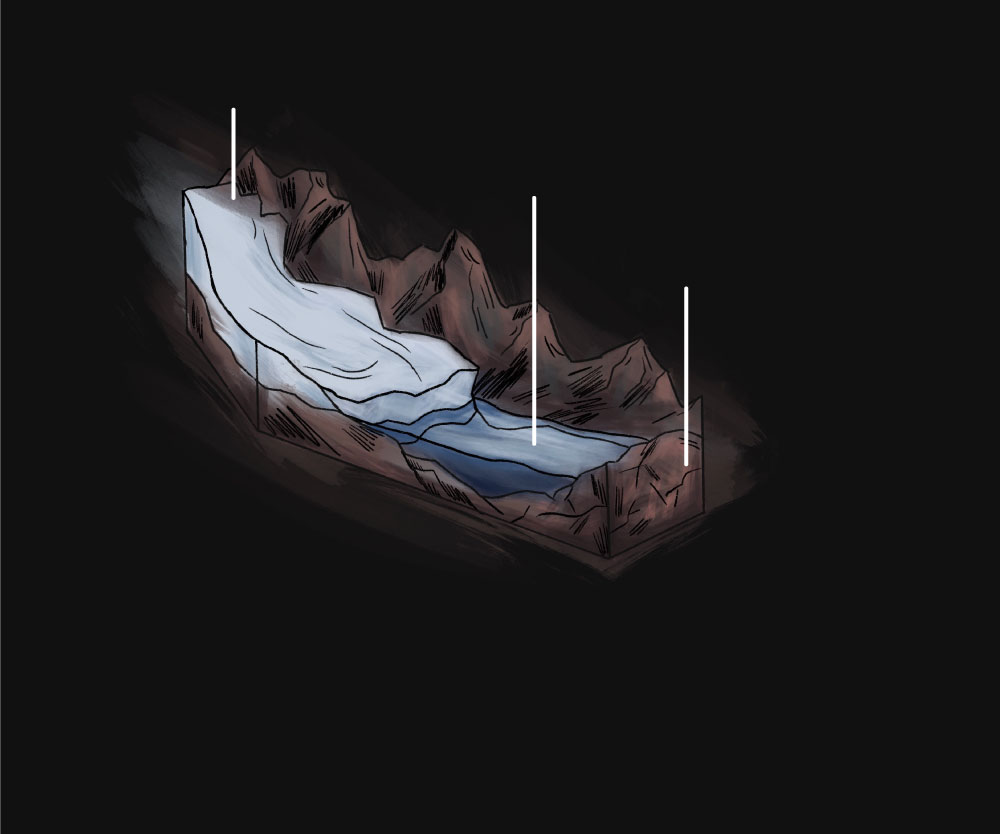

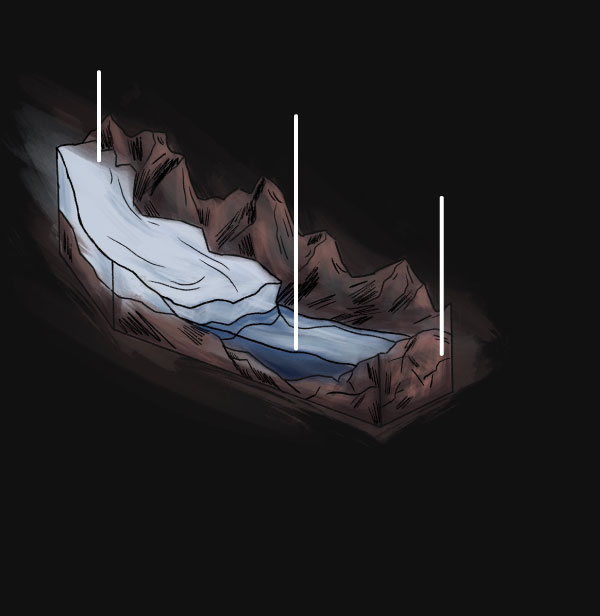

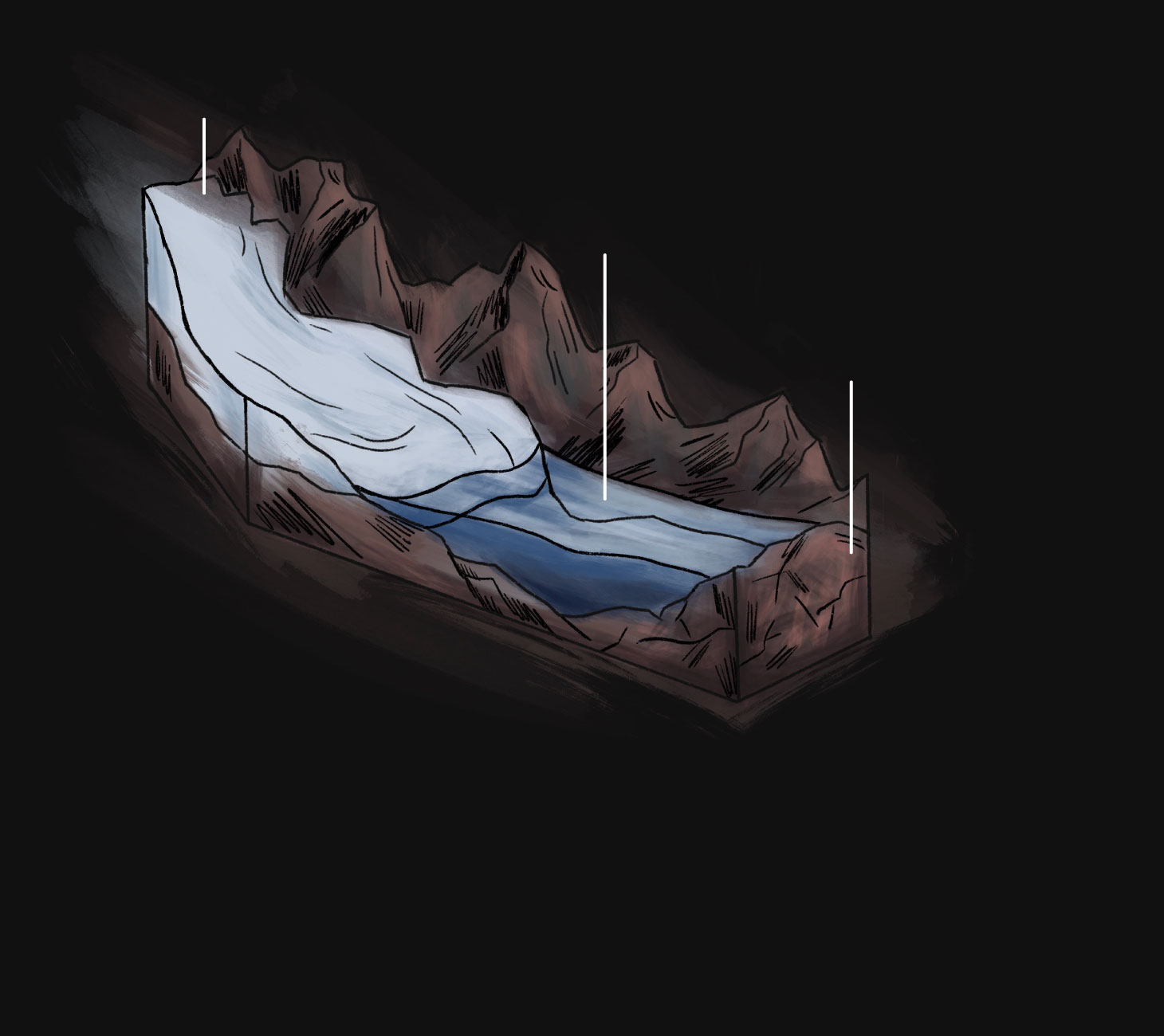

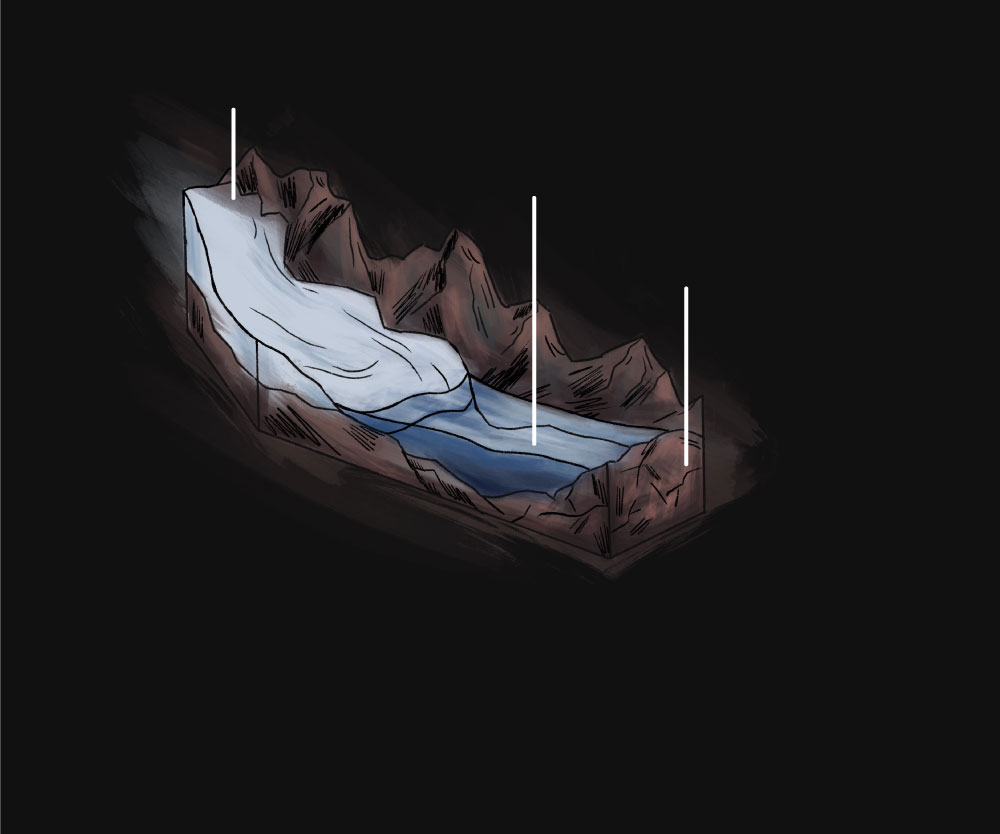

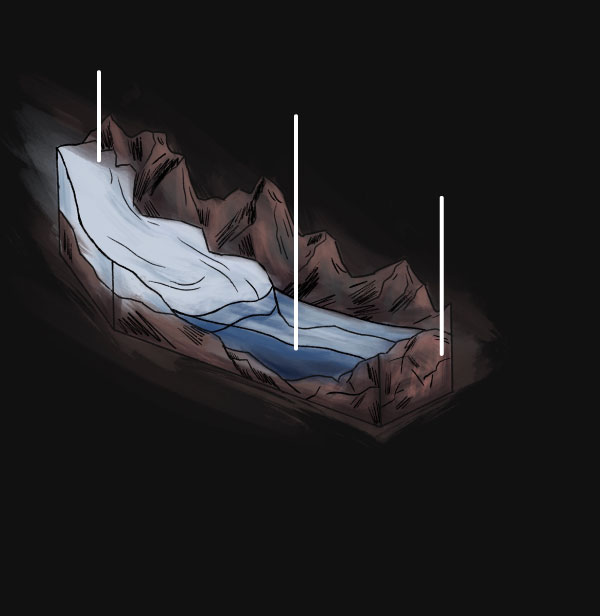

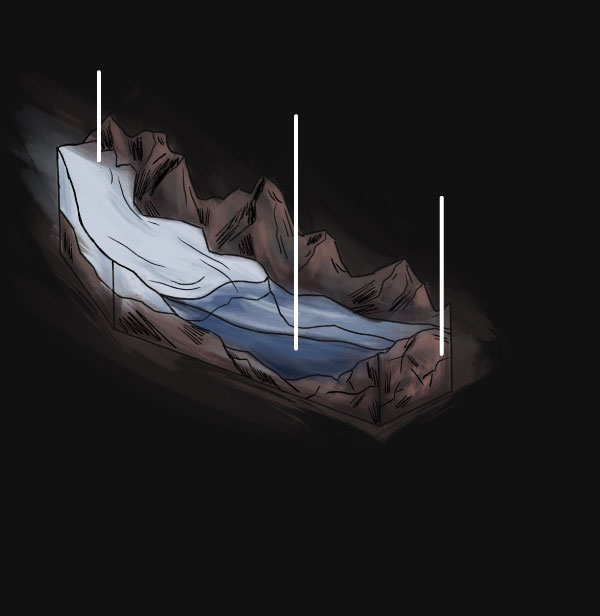

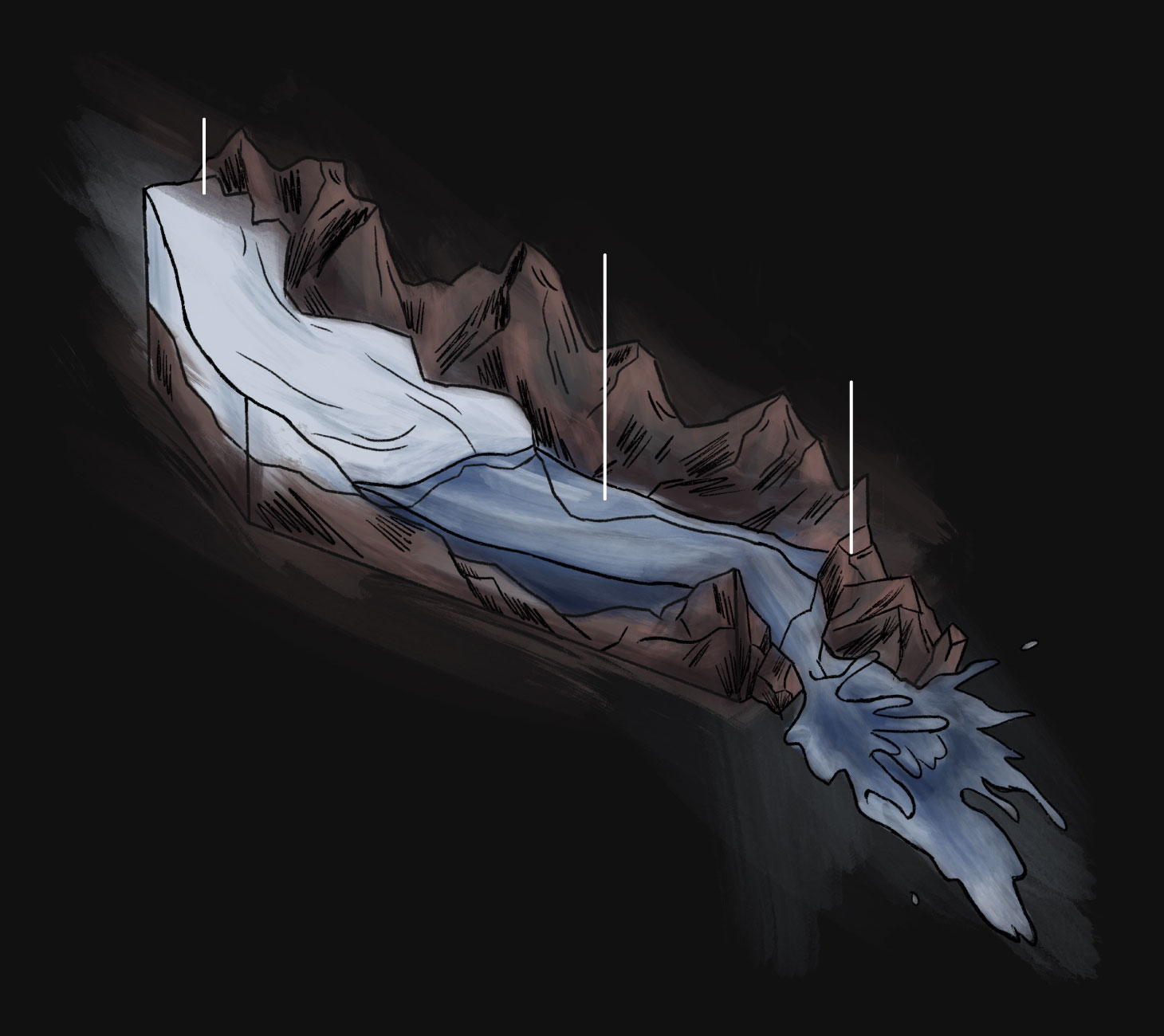

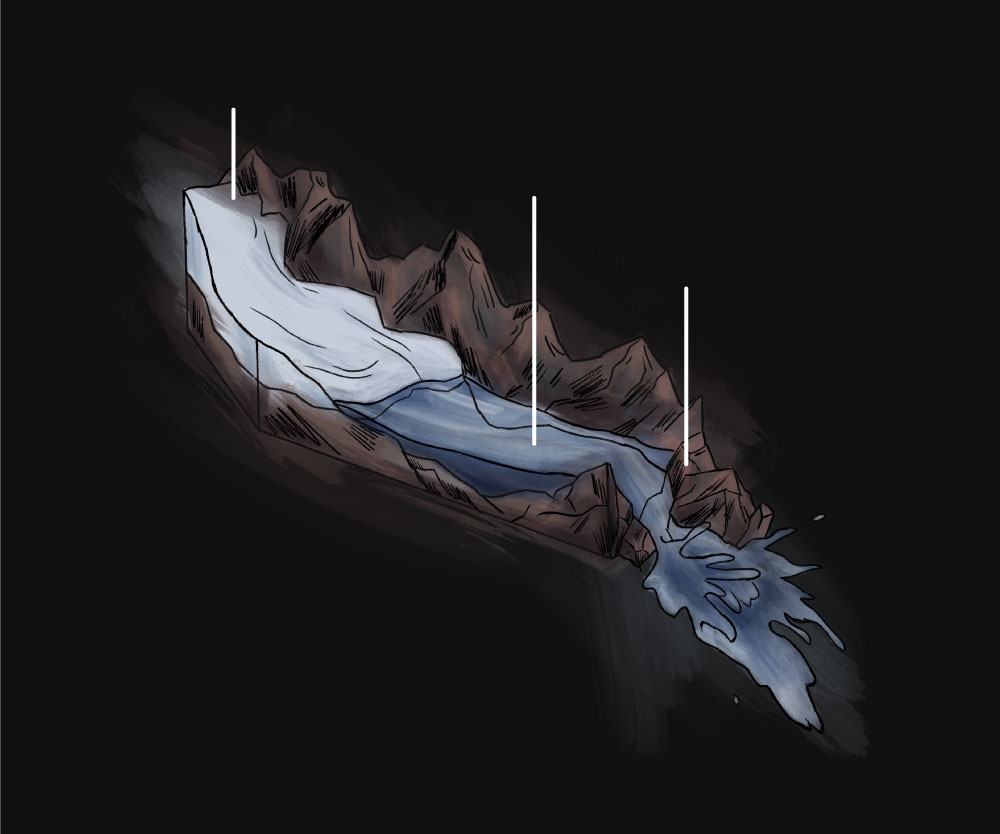

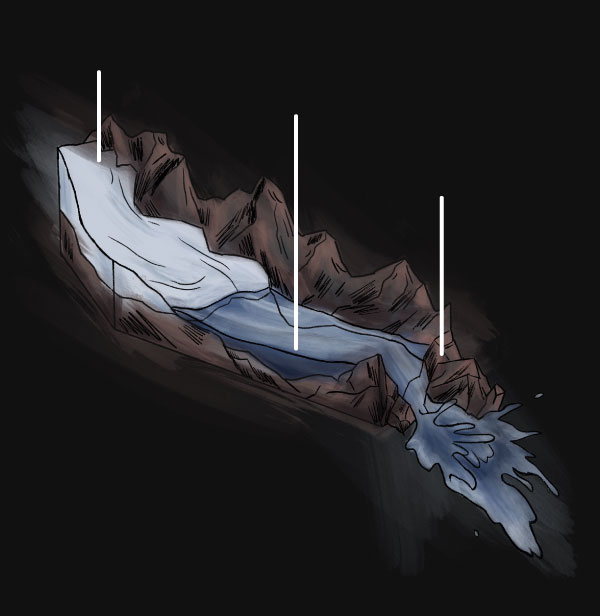

Glacier

Lake

Natural dam

Glacier

Lake

Natural dam

Glacier

Lake

Natural dam

Glacier

Lake

Natural dam

Glacier

Lake

Natural dam

Glacier

Lake

Natural dam

Glacier

Lake

Natural dam

Glacier

Lake

Natural dam

Glacier

Lake

Natural dam

Climate change is causing glaciers to melt in mountains around the world.

As the ice retreats, it’s leaving behind thousands of unstable lakes.

Glacier

Lake

Natural dam

Glacier

Lake

Natural dam

Glacier

Lake

Natural dam

Many of those glacial lakes are dangerous. The natural dams that hold them back can easily fall apart or be overwhelmed as a lake grows, releasing all the water at once.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

An estimated 15 million people around the world are threatened by floods from glacial lakes, according to recent research.

And the danger is growing as Earth heats up.

The Himalayan region is a hot spot for these disasters.

Flash floods from glacial lakes there have killed hundreds of people and destroyed roads, bridges, power plants and crops.

Last year, multiple glacial lake floods hit Pakistan, contributing to one of the deadliest disasters in recent history.

Glacial lake floods also threaten people in the Andes, the Alps and in multiple mountain ranges in the United States.

In Juneau, Alaska, the lake created by a receding glacier has caused a flood every year since 2011.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Nepal is ground zero for research about dangerous glacial lakes, in part because the mountainous country is on the front lines of the problem.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Climate change affects the mountains more severely than other ecosystems.

This region is warming at least twice as fast as the global average.

That means glaciers are disappearing and being replaced by potentially dangerous lakes.

Scientists from around the world have flocked to Kathmandu to join local experts, including glacial lake analyst Sudan Bikash Maharjan. He and his colleagues at the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development are racing to map the new lakes and figure out which ones pose the biggest danger.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Identifying dangerous lakes, and predicting when they might cause a flood, is incredibly challenging.

Many of the fastest-growing lakes are located deep in the mountains.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

The work is so time-consuming and remote that scientists haven’t even mapped out where all the potentially dangerous lakes are, let alone figured out when those lakes might release their water.

But scientists in Nepal have had some success by supplementing on-the-ground measurements with satellite images and data collected with aircraft.

This lake at the top of the Rolwaling Valley, which is called Tsho Rolpa, is one of the most dangerous lakes in Nepal, according to scientists.

The government says it is a “critical threat” — a flood here could kill everyone living immediately downstream.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

If the unthinkable happens, and Tsho Rolpa lake bursts, these villages would be gone.

Even a smaller release of water — for example, if the lake temporarily overtopped its natural dam — could sweep away buildings, livestock and people.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Furdiki Sherpa, 80, can see the edge of the lake from her home in the village of Na.

She has lived here all her life.

“I only want to live here,” she says. “Why would I want to live anywhere else? We have clean air, clean water.”

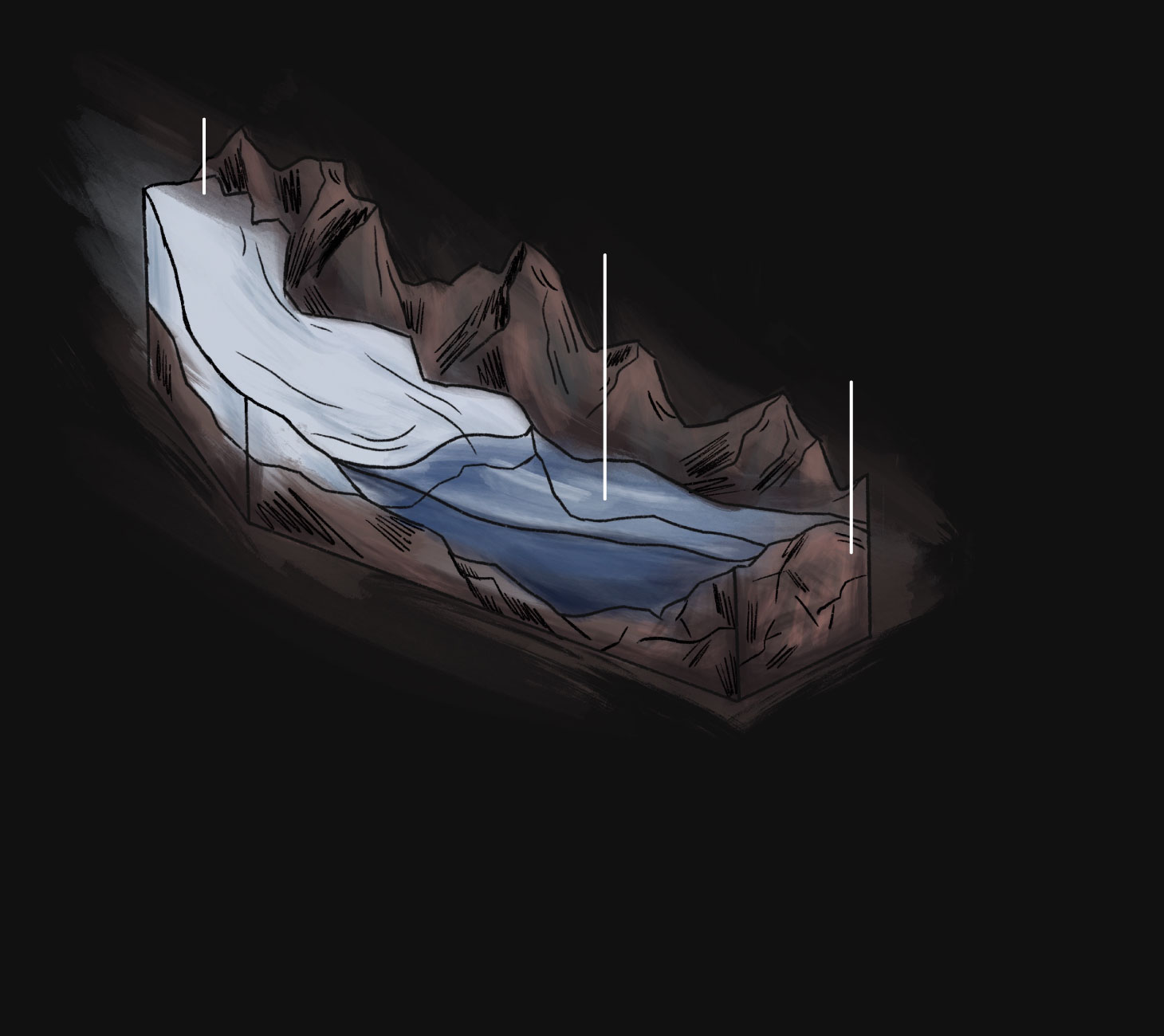

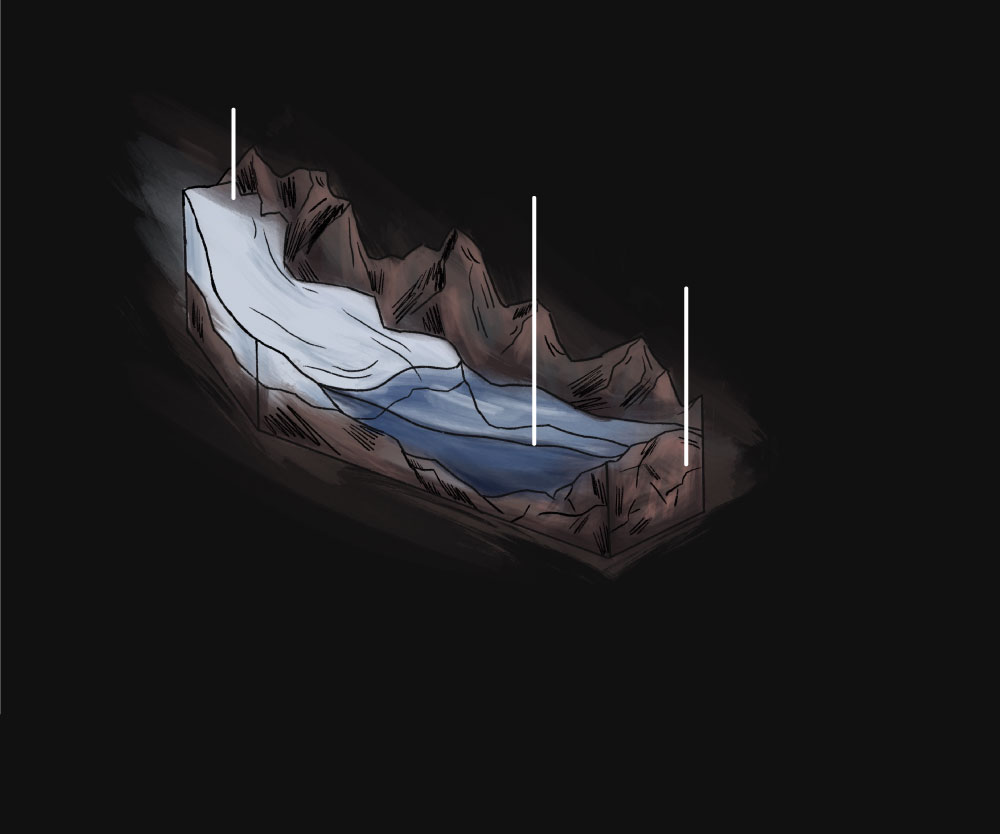

Lake size circa 1963

Lake size in 2022

Lake size circa 1963

Lake size in 2022

Lake size

circa 1963

Lake size in 2022

Lake size

circa 1963

Lake size

in 2022

Tsho Rolpa lake has formed within Furdiki Sherpa’s lifetime.

It went from a collection of small ponds to a deep, wide lake.

Today, it covers an area the size of about 300 football fields.

As the lake expands, it is eroding the mountain cliffs around it and putting pressure on the natural dam of rocks that holds the water back.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Many people who live downstream from Tsho Rolpa lake have voiced concern about the looming catastrophic flood.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

The valley has become an important example of how local residents cope with the risks posed by glacial lakes and how those who stand to lose everything in a flood can use scientific research to protect themselves.

Tilak Acharya was a longtime teacher in the largest town immediately downstream from the lake.

He led a successful petition in the early 2000s to install warning alarms that would be triggered if the lake was about to release its water.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

But the government has not been able to maintain the alarms, which are many days’ walk from the nearest road. Today, most of them are broken.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Local concern about the lake also led research scientists and hydrologists working for Nepal’s government to design and build a massive system to slowly drain water from the lake. The goal is to prevent, or at least delay, disastrous flooding.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

“We got the attention of everyone in Kathmandu,” says Tilak Acharya, the former teacher who helped lead the local effort.

He says the flood control infrastructure bought the valley some time. “It helped a lot.”

But long-term it won’t be enough to prevent a flood. The lake is still growing.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Still, many residents feel safe, despite the flood risk.

Nima Sherpa, 91, is the oldest person living in the village of Beding, which is just a few miles downstream from the lake. She says she regularly makes the three-hour hike to the lake for fun.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Sherpa says she has heard the warnings about a potentially massive flood in the future. “If it happens after I die,” she says, laughing, “it doesn’t matter.”

Plus, she adds, “This is a village that is protected by the gods. So nothing bad happens in this area.”

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

The leader of the valley’s main monastery, Rinpoche Ngawang Tenzin Lama, says he doesn’t think residents should be afraid of Tsho Rolpa as long as everyone keeps the lake clean and treats it with respect.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

The Rinpoche has met with climate scientists who are studying the lake and heard their warnings about flooding. He is not concerned.

“Tsho Rolpa is pure. It is sacred,” he explains. “We don’t disrespect nature here. We do not have any factories. There is nothing to cause the lake to flood so soon.”

But people living far from here have a different relationship to nature.

And they may have sealed the fate of this valley.

Human greenhouse gas emissions are the cause of Nepal’s melting glaciers. The lake exists because of human pollution.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

And that connection is clear to some residents of the valley.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

“We are not the people polluting the environment. It’s factories in cities, especially out in the bigger world,” says local schoolteacher Bolendra Acharya. “It’s not people like us, living in rural areas, that are contributing to the damage of Earth.”

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Still, it can be difficult to imagine a catastrophic flood hitting a place where your family has lived safely next to the river for generations.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Chenga Sherpa lives in the village of Dongang with her husband, children and grandson.

The family runs a trekker hostel that is just a few yards from the edge of the river.

During the height of the pandemic, when there were no customers, Sherpa and her family invested everything they had to expand the business.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Their 18-year-old son, Lhakpa Sonam Sherpa, plans to take over the business and make it his lifelong career. “This is what I want to do, and this is where I want to live,” he says.

“I don’t think the water will burst out,” he continues. “It never did in the past.”

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

But no matter how deep their ties to this valley, other residents say the lake is just too dangerous. They cannot keep living downstream.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Over the last two decades, many young people have left the valley to live in Kathmandu. Local leaders say the threat of flooding is one reason for the exodus.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Even within families, people disagree about how to cope with the flood risk.

Ang Tenzing Sherpa, 74, has been married to his wife, Furdiki, for four decades. They have seven children and nine grandchildren, some of whom still live in the valley.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Furdiki says she will never leave.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

But Ang wishes he could.

“All summer, I can’t sleep. Every sound, I wonder if it’s the lake finally releasing its water. I lie down in my clothes every night, in case I need to flee.”

Scientists hope that in the coming years they will be able to monitor lakes like Tsho Rolpa in real time, with automated instruments that can warn residents if a flood is imminent.

And efforts are underway to expand glacial lake monitoring around the world.

That could protect millions of people from catastrophic floods.

It will also thrust more communities into the uncomfortable conversations that residents of the Rolwaling Valley are already having, about what to do when your home faces an existential threat.

And whether to stay or leave.