Some of the fastest sea level rise in the world is happening in Galveston, Texas.

Maybe you imagine sea level rise like a bathtub, with the water rising equally everywhere.

But it’s way more complicated. Different places experience very different amounts of sea level rise.

By 2050, Galveston could experience more than 200 days of flooding every year.

But what will happen beyond 2050 is more of a mystery.

Icefin/ITGC/Mullen

Icefin/ITGC/Mullen

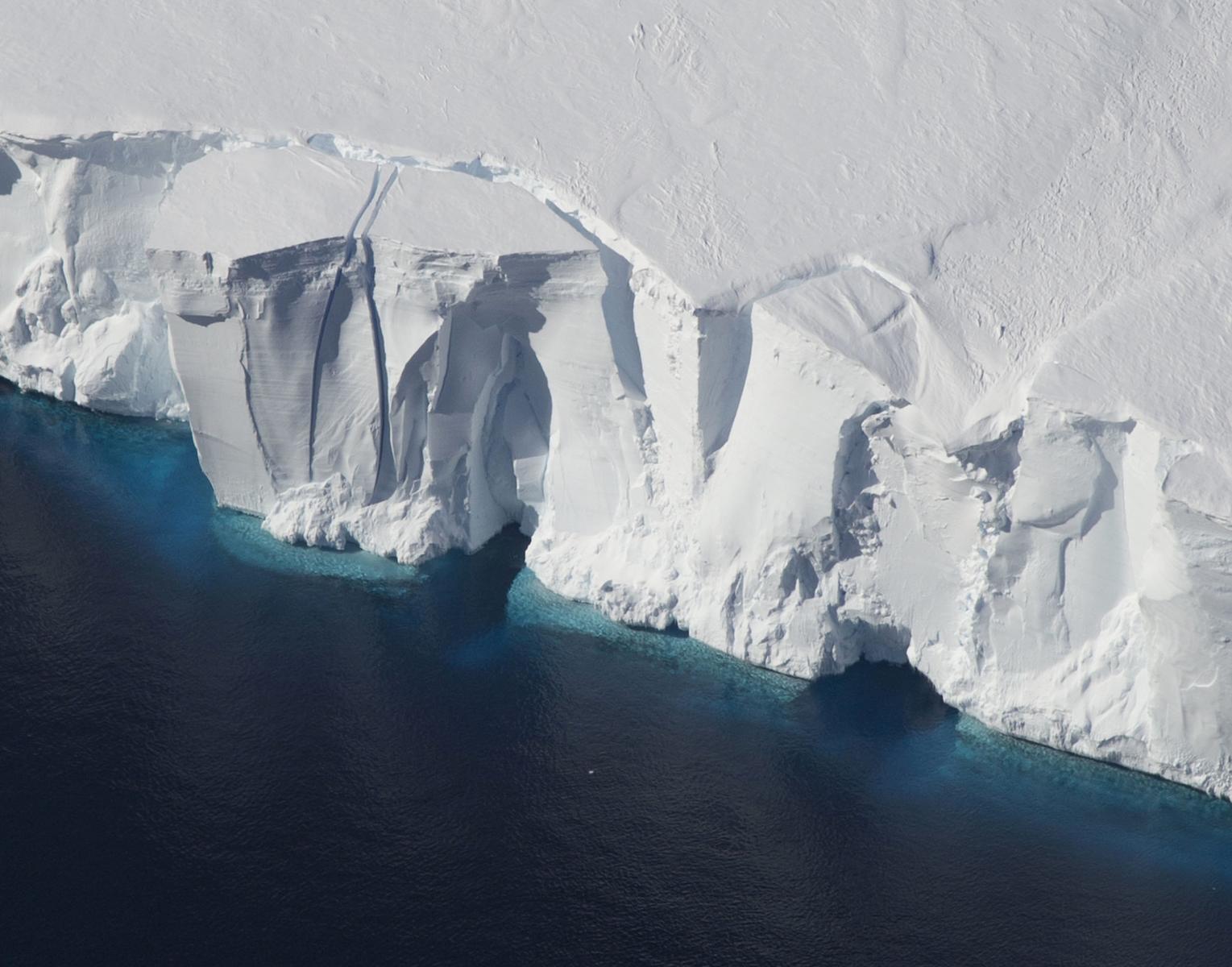

One of the hints about Galveston’s future lies 8,000 miles away, where scientists are camped on top of the massive Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica.

They are racing to measure how quickly the glacier and the ice surrounding it are disintegrating.

Will this place crumble in 10 years? 50 years? 500 years?

How fast will the ice melt?

How fast will the water rise?

These are not separate questions.

What happens in Antarctica will have profound effects in Texas.

Why Texans need to know how fast Antarctica is melting

West Antarctica contains enough ice to raise global sea levels by more than 10 feet. But the ocean is not a bathtub: Antarctic melt affects some places more than others.

And Galveston, Texas, is in the crosshairs.

Reporting by Ryan Kellman and Rebecca Hersher

Galveston, Texas, is on an island in the Gulf of Mexico.

The city of about 50,000 people is a popular vacation destination and the gateway to one of the busiest petrochemical corridors in the world.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

As sea levels rise, the city is grappling with existential flood risk.

The worst-case scenario would be a direct hit from a hurricane. Storm surge combined with sea level rise could flatten the city.

Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

That disaster has happened before in Galveston.

On Sept. 8, 1900, a Category 4 hurricane hit the island with a 15-foot wall of water.

At the time, Galveston had more millionaires than any other city in America.

Much of the island was destroyed. At least 6,000 people died.

It’s still the deadliest weather disaster in recorded U.S. history.

Annie Smizer McCullough and her family escaped from their home as the water rose. She was 22 years old at the time.

The horror of the storm was still fresh when she remembered it 70 years later for an oral history interview.

“Oh, it was an awful thing. You want me to tell you, but no tongue can tell it …,” she said. “The wind was so strong and those waves was coming.”

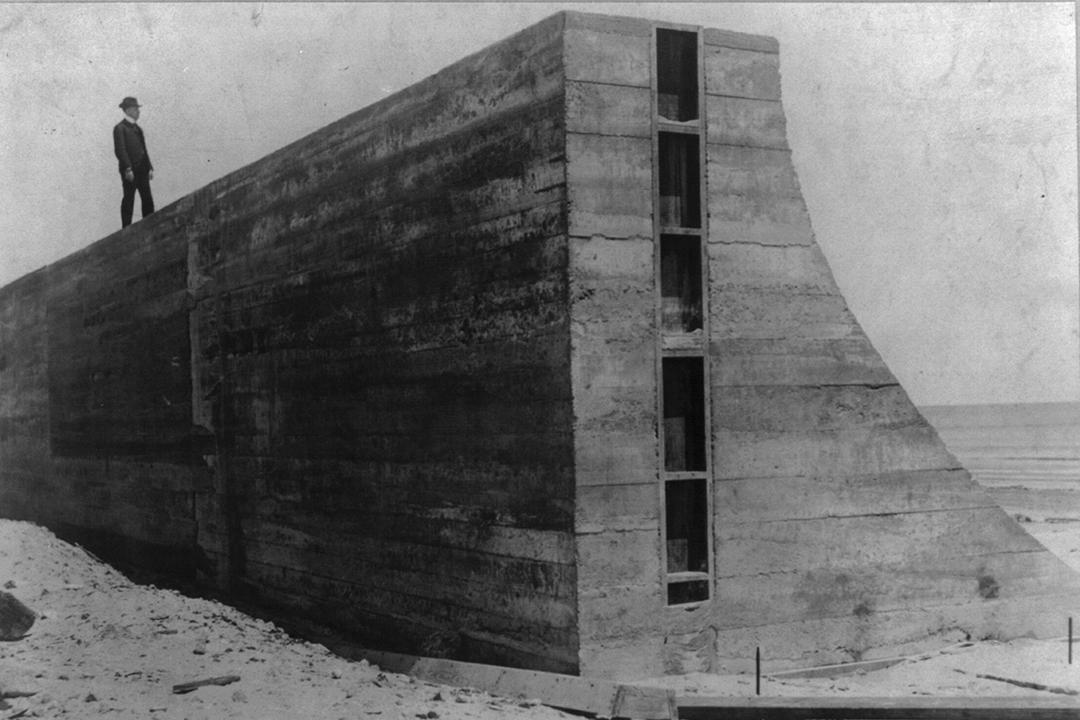

Engineers had a plan to protect Galveston from future storms: The government constructed a 17-foot-tall concrete sea wall that eventually ran the length of the city facing the Gulf of Mexico.

Underwood Archives via Getty Images

Underwood Archives via Getty Images

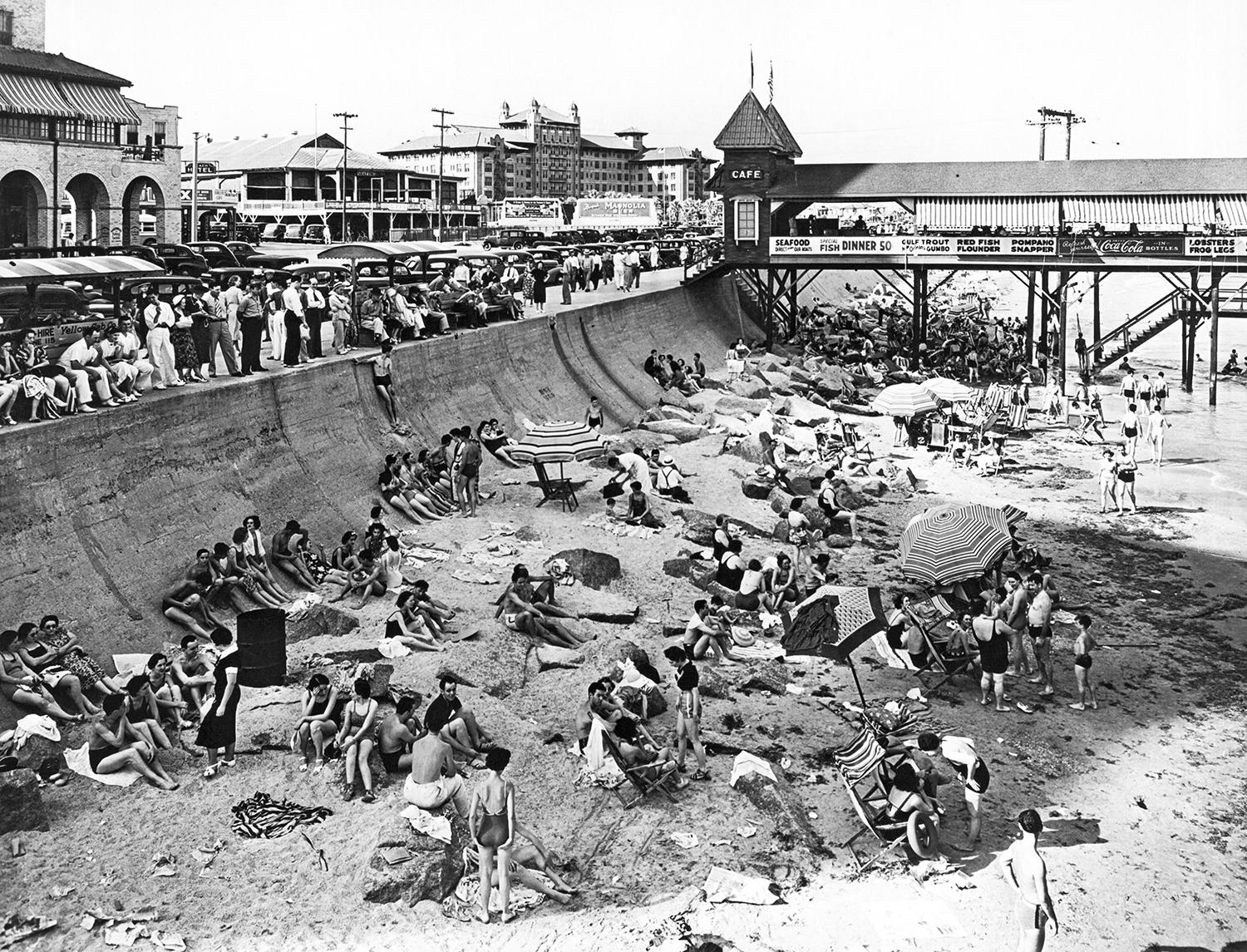

Within a few years, the city was thriving again.

Residents and engineers thought the sea wall would protect the city forever.

Maybe it would have done the trick, if not for climate change.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

The problem is that sea levels are rising faster in Galveston than almost anywhere else in the world.

Connie Hanzhang Jin/NPR

Connie Hanzhang Jin/NPR

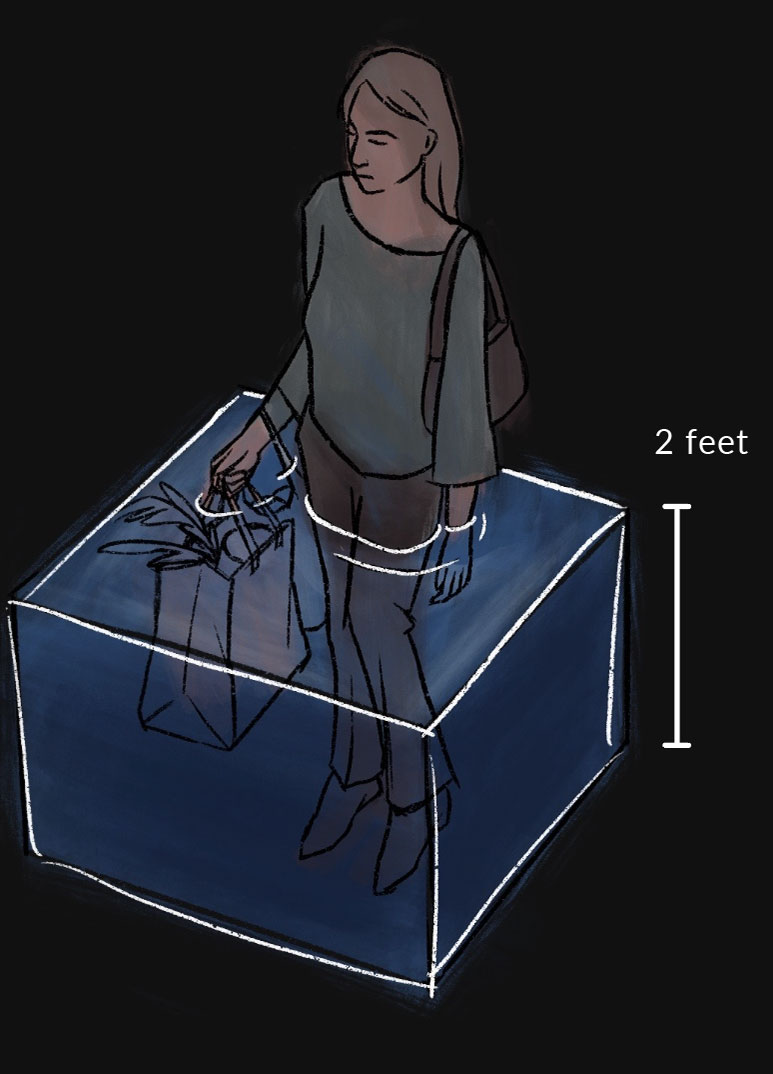

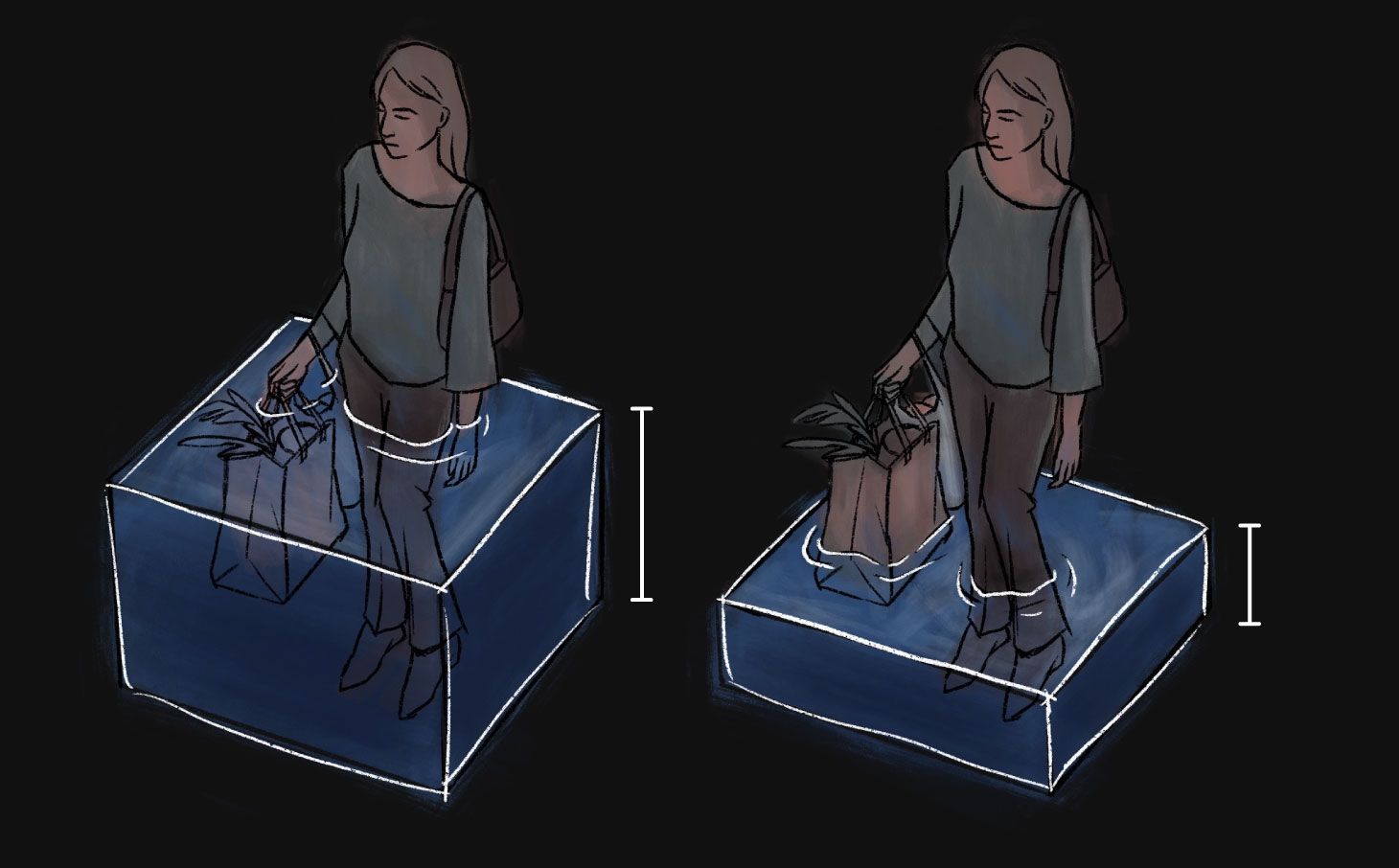

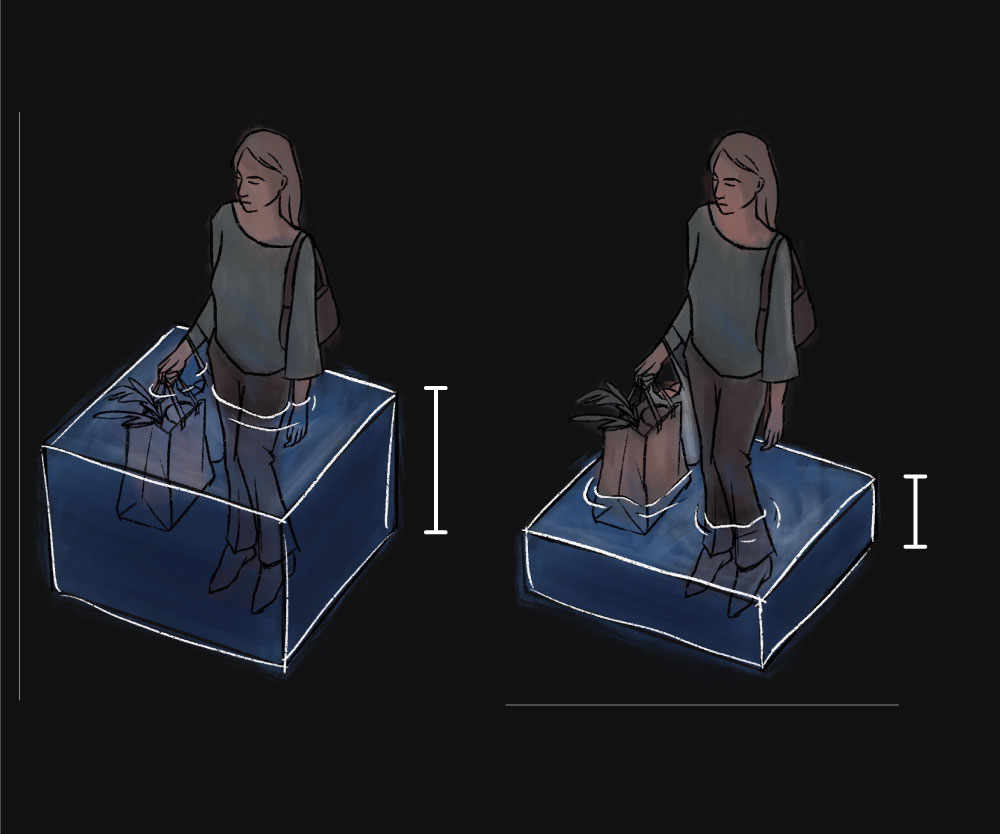

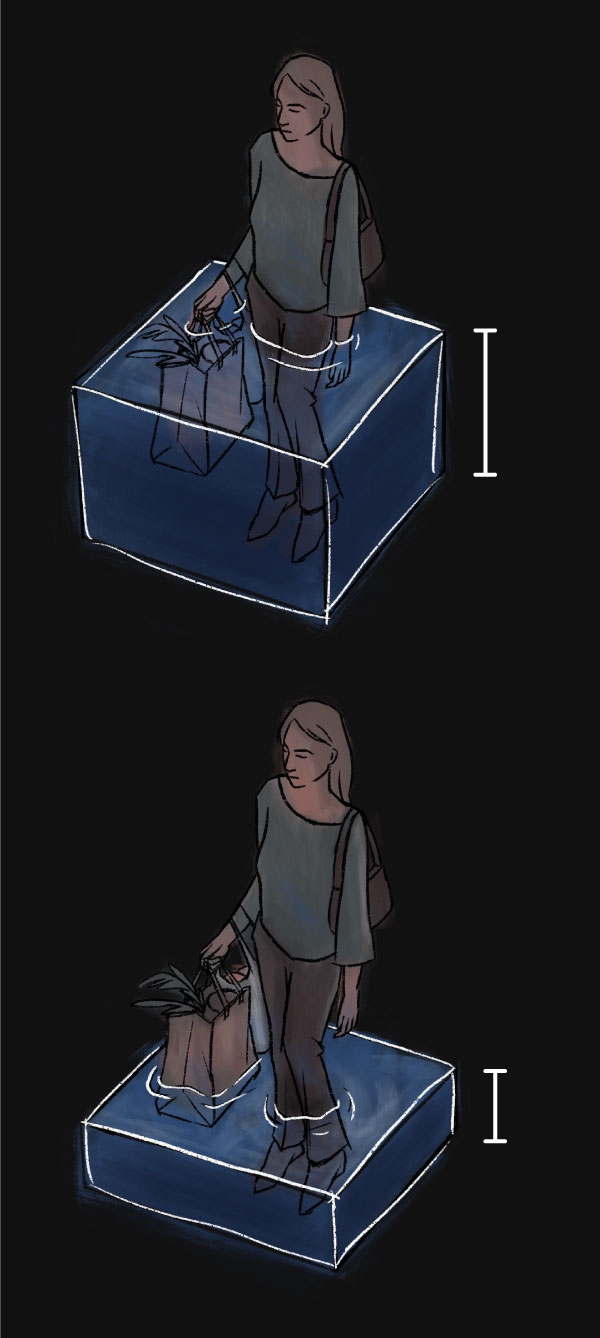

There has been more than 2 feet of sea level rise in Galveston in the last 100 years.

Connie Hanzhang Jin/NPR

Connie Hanzhang Jin/NPR

The global average during that time was about 8 inches of sea level rise.

2 feet

8 inches

2 feet

8 inches

2 feet

8 inches

There has been more than 2 feet of sea level rise in Galveston in the last 100 years.

The global average during that time was about 8 inches of sea level rise.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

All that water is threatening the city.

Homes built beyond the sea wall are already being destroyed by rising seas.

Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post via Getty Images

A big wake-up call came in 2008, when Hurricane Ike made landfall just outside Galveston.

Sea level rise contributed to catastrophic flooding. The storm surge was up to 17 feet high.

Matt Slocum/AP

Matt Slocum/AP

Experts warned that if Ike had taken a slightly different path, it would have overwhelmed the Galveston sea wall.

The city could have been destroyed. Again.

So, 108 years after the Great Storm of 1900, Galveston was back to square one.

And engineers reacted the same way they had more than 100 years earlier: with plans for a wall.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Today, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has a $34 billion plan to build taller sea walls, gigantic new ocean gates across a 2-mile channel, and miles of man-made dunes.

The goal is to protect Galveston, Houston and dozens of Texas communities in between.

The Corps estimates the project would take about 20 years to build.

“This will be the largest-ever civil works project undertaken by the [Army] Corps of Engineers in its 220-year history.”

— Kelly Burks-Copes, project manager for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Coastal Texas Program

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

But the Corps acknowledges that the new protections won’t necessarily be enough to protect Galveston for another 100 years.

It all depends on how quickly sea levels rise.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Figuring out how quickly seas will rise is a life-or-death question.

And it falls to scientists to answer it.

This is the most sophisticated estimate of future sea levels in Galveston.

We know how much sea levels will rise by 2050: about 2 feet.

But see how the lines split apart after that?

There’s a big range of possibilities.

One hundred years from now, will there be 3 feet of sea level rise in Galveston? 11 feet?

The answer partly depends on how much carbon dioxide humans pump into the atmosphere.

Unfortunately, we can’t predict how human greenhouse emissions will change.

But the answer also depends on how ice caps respond to global warming. And there’s a lot we can learn about that.

Studying how, exactly, ice sheets melt helps us better predict how much water could flow into the ocean, and when.

And that’s why what happens in Antarctica will matter to Texans.

Jeremy Harbeck/NASA

Jeremy Harbeck/NASA

Even though Texas is nearly 8,000 miles from Antarctica’s western region, melting ice there will be the main driver of potentially catastrophic sea level rise in the Gulf of Mexico later this century.

Here’s why.

The West Antarctic ice sheet is huge — it contains enough water to raise global sea levels by more than 10 feet.

As Earth heats up, melting at the bottom of the globe will accelerate, and Antarctica will become the biggest source of extra water for much of the U.S. coastline.

And here’s something surprising:

Antarctica has a special relationship with the East and Gulf coasts of the U.S.

Melting ice in West Antarctica disproportionately affects Texas, in part because they are connected by major ocean currents.

Research suggests that all of the meltwater pouring off West Antarctica could cause currents near the U.S. to slow down and spread out later this century.

That could push even more water toward the Gulf of Mexico.

But there are still big unanswered questions about how quickly West Antarctica will pour its water into the ocean.

One piece of West Antarctica is of particular interest because it is so large and is melting so quickly. It’s called Thwaites Glacier. It’s larger than the state of Florida and acts as a plug, holding back even more ice behind it.

Hundreds of scientists from around the world are studying it.

Thwaites is falling apart before our eyes.

Giant cracks in the surface of the glacier, like you can see here, are forming twice as quickly now as they were just a few years ago.

No one knows why the cracking is accelerating.

“We are trying to understand what could have triggered that,” says glaciologist Erin Pettit. “Something changed, but it’s not obvious what.”

Pettit spent nearly a month camped on the glacier earlier this year, living in tents with her colleagues and braving storms and freezing temperatures.

She was there to gather crucial measurements about how quickly cracks are forming and what is happening deep within the ice as it melts and fractures.

Nathan Kurtz/NASA

Nathan Kurtz/NASA

Glaciers are not like ice cubes in the sun, gently liquifying.

Instead, melting glaciers are dynamic, unpredictable, sometimes-violent places. The ice at the surface interacts with the sun and the wind. Even algae affect how quickly the ice at the surface turns to water.

Cracks spider along the surface and shoot up from below. If two cracks meet, an entire section of the glacier can splinter with little warning.

Glaciers change slowly. And then suddenly, all at once.

Emelie Mahdavian

Emelie Mahdavian

That is why it’s so hard to predict exactly how quickly the ice in Antarctica will melt, Pettit says.

That makes it hard to know how quickly sea levels will rise in Texas.

And it underscores an uncomfortable truth about climate change: We don’t understand everything about it. But if we wait for all the answers, it will be too late to adapt.

Preparing for future sea level rise is like building a ship while you’re sailing it into an unknown storm. The design needs to be flexible. But if you don’t start immediately, you’ll drown for sure.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

Ryan Kellman/NPR

So plans to protect Galveston are moving ahead.

In December, Congress greenlit the Army Corps’ $34 billion plan for massive walls, dunes and gates. Some parts of the design are built specifically to support future upgrades — a nod to what we don’t know.

“Everything’s been happening a lot faster than we expected it to. What might Antarctica do in the next hundred years?

“All we have power over is our own actions and our own decisions.”

— Erin Pettit, lead scientist for a research mission to Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica

“You can’t be paralyzed by uncertainty. You have to actually start making decisions.”

— Kelly Burks-Copes, project manager for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Coastal Texas Program